I was talking recently to a friend in the publishing industry, who’s helping me with a proposal for what I hope will become my next book.

“You’ve written books about drum machines and philosophy, about the Beastie Boys and the American Revolution.” She paused and laughed.

“Your career makes absolutely no sense.”

It was a good-natured, tongue-in-cheek observation, yet I could hardly deny the truth in it. She has a point…one I’ve thought about often. Somehow, I’ve managed to follow the same sort of path that has led many of the musicians I admire to colorful and utterly confounding careers.

The great philosopher Ed Feser was kind enough to say earlier this year that I am “an author of admirable range.” When I’ve written that kind of praise in a music review before, it’s usually about an album guaranteed to lose its creator a record deal.

The thing the creator will alway say about their path is that it makes perfect sense…to them. I’ve done enough interviews over the years where musicians have told me just that. And I suppose the same is true of me.

But it got me thinking—not for the first time—about the connections between my interests. Specifically, between the last two books: about drum machines and philosophy.

One of the standard questions I asked my more than 130 interviewees in Dancing to the Drum Machine was whether there is still a place for the standalone drum machine in a world of plug-ins and digital sound creation.

What I found interesting—though perhaps not surprising—was the view of many older musicians. These were the guys who’d had to go through painstaking processes to use drum machines, pre-MIDI, and who’d also had to lug around huge collections of equipment for years and years. So quite a few were enthusiastic about the move away from physical machines.

Here’s a quote from an interview with hip hop pioneer Ben Cenac, in Dancing to the Drum Machine:

Some who used this technology the first time around feel they’ve suffered enough. “I don’t need to do that shit no more,” says Ben Cenac of Newcleus, roaring with laughter. “I paid my dues with that shit!” More seriously, Cenac says, computer plug-ins that simulate the sound of drum machines and other instruments “are getting better and better all the time.” e average listener, he points out, can’t tell the difference, especially in a world where users are used to the compressed sound of MP3s and streaming audio.

In lots of other conversations, musicians turned a standard idea—that older musicians always believe things were better in the past—on its head. I lost track of the people who told me (sometimes sadly; more often, not) they no longer had any of their old gear, drum machines especially. In some cases, they’d simply given it away, or had no idea what finally happened to these machines. As Will Sergeant of Echo and the Bunnymen told me, the band’s drum machines “all get stolen or left behind or broken or forgotten about.” (He did sound rather morose when he said this.)

Conversely, quite a few younger musicians expressed fascination with these supposed relics of a bygone era. I think of Ministry and Stone Sour drummer Roy Mayorga, who enthused about his drum machine collection—which includes a copy of his first drum machine. That was the Mattel Synsonics drum kit, the best present he received for his twelfth birthday.

On first hearing the Synsonics kit, “I flipped out,” Mayorga said, a huge smile on his face. “There’s my answer to Kraftwerk!”

(At the time, Mayorga didn’t know that Kraftwerk has actually used this humble device. At some point, I hope to write about the number of people for whom the Synsonics kit—which was marketed like a toy; you could find it in the J.C. Penney Christmas catalog—was the entry into electronic percussion. Mayorga, electronic musician Moby, and—ahem—your author are just three such examples. Don’t circle the one that doesn’t belong.)

So what does all that have to do with philosophy?

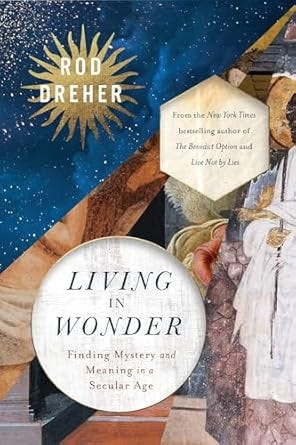

I was thinking about all earlier this week, in Birmingham, Alabama, at the book release for Rod Dreher’s latest, Living in Wonder. The thesis of the book is, roughly speaking (very roughly; I’ve just started reading it), that the modern world has become dis-enchanted. That is, cut off from any sense of divine wonder.

And one of the primary reasons, in Dreher’s reckoning, is that the modern world is one in which matter—physical objects—are just things to be manipulated. Believing that all matter is subject to our every whim is bad at a number of levels.

For one, it makes things (including human beings) less inherently special. They’re just stuff, to be changed/altered/edited whenever and however we feel like it.

For another, this belief—which I wrote about in my latest book, Why We Think What We Think: The Rise and Fall of Western Thought—makes our grasp on reality more and more tenuous. We don’t see things for what they really are: we’re only interested in how we can control them. And of course, this delusion that we can reshape reality to suit us gains more and more traction in an increasingly digital world.

As the British philosopher and scientist Sir Francis Bacon put it, way back in the early seventeenth century, “Knowledge is power.” In other words, knowledge wasn’t valuable for its own sake. It was valuable because it allowed us to predict and control nature. And we’ve been doing it ever since.

Psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist took up this subject in his 2021 book The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World—a book Dreher mentioned as being influential in the creation of his own work.

Perhaps the key quote from The Matter With Things is this. McGilchrist believes that today’s world is left brain-dominant—to its detriment. He writes that “the brain's left hemisphere is designed to help us ap-prehend—and thus manipulate—the world; the right hemisphere to com-prehend it—see it all for what it is.”

In short, we’ve lost the ability to see the world for what it is, and can only view it as what it could be—once we’ve manipulated it to our liking.

So what does all that have to do with drum machines?

This, I think. In the chase for perfection—audio perfection is just as seductive as every other kind—we lost sight of exactly how special, and how human, those little boxes were.

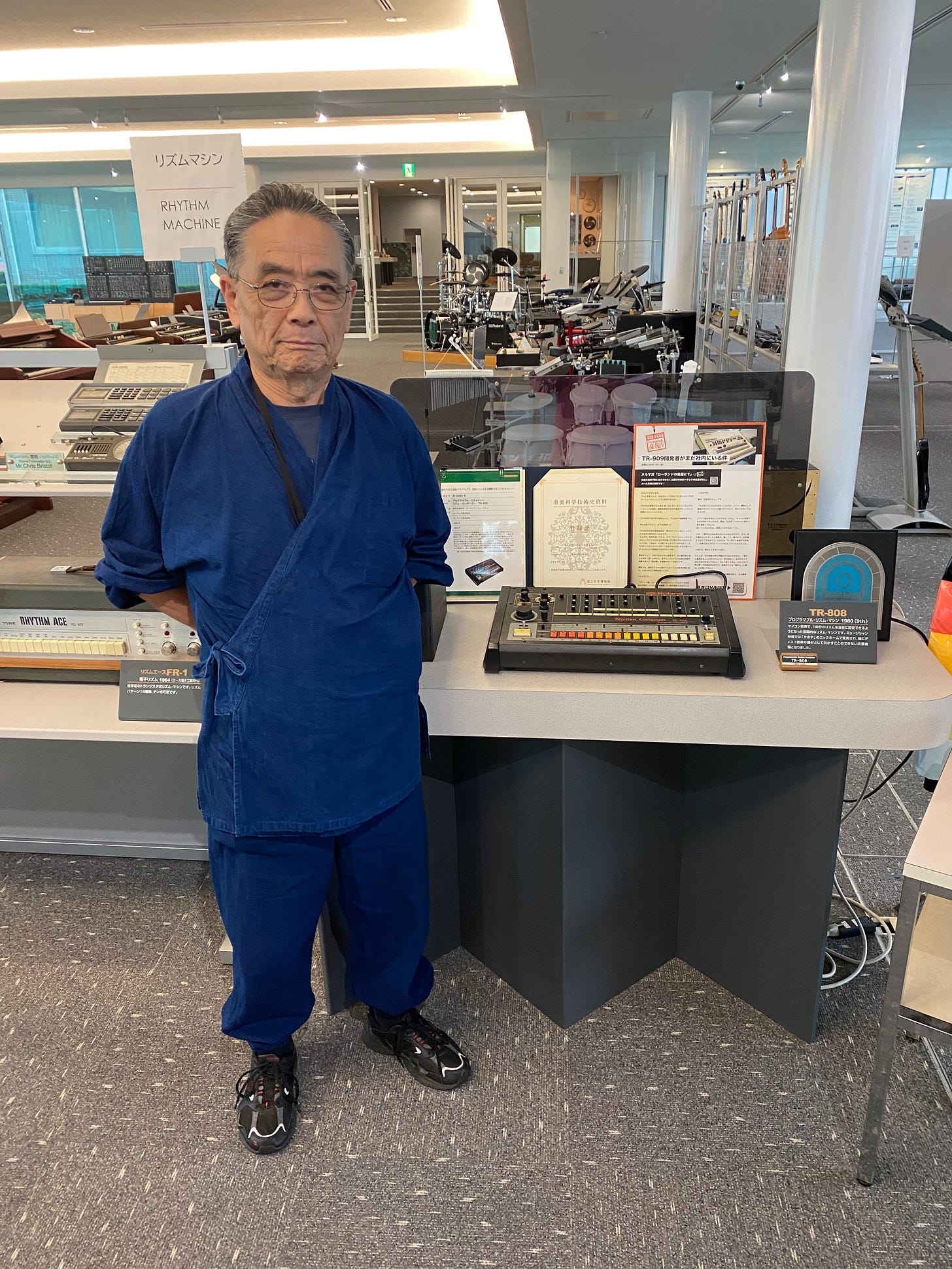

Earlier this month, I had the great good fortune to visit the Roland Electronics museum in Hamamatsu, and to spend a day with Tadao Kikumoto, the electronics genius largely responsible for creating the iconic Roland TR-808 and TR-909 drum machines.

(The facility is private, but you can see at least some of what I saw here.)

Walking around the empty museum on a rainy autumn afternoon, Lake Hamana stretched serene outside the floor-to-ceiling glass windows, it was hard not to be amazed. Kikumoto-san and our interpreter, Taro Araki, paused beside the different displays and shared recollections of the devices’ individual histories.

As Kikumoto-san stood next to what many would argue is his greatest creation, the 808, I was reminded of a story from my book. The hip hop pioneer Man Parrish was telling a story about a special feature of this special machine:

(W)hen the TR-808 finally became available, Parrish immediately recognized the value of a particular feature: the fine tempo knob. It provided more precise control over the speed of a drum track than the “coarse” control, which had forty click-stop settings. This was important because when instruments couldn’t be made to sync on tape, Parrish had to make minute adjustments by hand to bring everything in line. “That really made a difference,” he says. “As the circuitry would heat up, as the tape would stretch, the beats per minute would go out of time. And I would ride that fine tempo knob like a DJ.”

Making small corrections, Parrish would try to keep the drums locked to the rest of the track for as long as possible. “Maybe you’d get 12 or 15 bars out of it, if you were lucky. Then it’d go out of sync, you’d stop the tape, roll it back a little, and start again. And I was the master of hitting the 808 on the downbeat to start it back up.” He sighs. “But that was not a lot of fun.”

The book is full of stories like this—tales of human ingenuity overcoming mechanical limitations. These are the sorts of tricks you no longer have to perform when everything is digital.1 And as a result, I think something important has been lost, in this transition away from the realities of the material world to the promise of the virtual one.

Just looking at the machines themselves was another reminder of this shift. The 808 is the obvious example. If you’ve seen one, then you know that the rows of red, orange, and yellow buttons at the bottom weren’t just functional (they made step programming of rhythms easier). They also gave the machine a colorful aesthetic that became so well known that it was later adopted into clothing and shoes.

In short, it’s a beautiful piece of technology. There are inherent limits to what it can do. But within those limits, entire musical worlds have been created. And it speaks directly to the great and persistent paradox of creation—that accepting limits enhances, rather than detracts from, the creative impulse.2

I’ll be writing much more about my trip to Japan in this space—and others—soon. But I realized that at least some of what I saw fit pretty neatly into this bigger question about the links between my various interests.

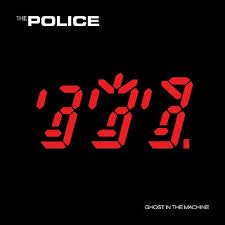

Fans of The Police (the band) will recognize the term “ghost in the machine.” They may know that Sting borrowed it from a 1967 book by Arthur Koestler (who also wrote the classic Darkness at Noon). Not everyone realizes the term originated with the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle—who used it to criticize the view that the mind and body are completely separate entities.

That’s a view popularized by the 17th century philosopher Rene Descartes (of “I think, therefore I am” fame), though it stretches back to the ancient Greeks. It’s also a view that is mistaken, in my opinion (as well as Ryle’s), and the source of much confusion in the 400-plus years of “modernity.”

So my inversion of the term as “machine in the ghost” is, for me, a reminder that while the concept of perfect rhythm has fascinated people for centuries, the realization of that concept—through rhythm devices of various types—is what’s truly interesting and remarkable. Losing these “machines in the ghost” means losing something—to cite another paradox—that makes us truly human.

Hey, I doubt all that will make many drum machine fans want to pick up a survey of Western philosophy—or vice versa. However, if you happen to be so inclined, I hope you’ll let me know what you think!

Isn’t this just “manipulation” of matter? In one sense, it obviously is. But in another sense, musicians of this era had no choice but to accept the technology as it existed. And while its shortcomings could be frustrating, in the longer term, accepting the machines for what they were often led to unexpected—and delightful—outcomes.

The entire history of the Roland TR-808, which I cover in Dancing to the Drum Machine, is a case in point. Some people complained early on because the 808 didn’t sound like “real drums,” the way its competitors, the Linn LM-1 and LinnDrum, did. Yet the impressionistic drum sounds that the 808’s engineers created were so striking and unusual that they became ubiquitous. Today, you hear them everywhere. To me, that’s an example of how “comprehending,” rather than “apprehending,” can be a worthwhile way of interacting with the world around us.

This is, of course, one of the hardest truths for young people—I’m thinking of my students over the years—to accept. But I recall a conversation I had recently with a well-known musician who admitted that scrolling through pages and pages of archived kick drum and snare drum sounds, available via plug-in, kills, rather than sparks, the creative impulse. “Too many choices,” he admitted. “It just makes you not wanna do anything.”