The Drum Machine Police

A fascinating new reissue is a reminder of The Police’s arresting adventures in programmed rhythm

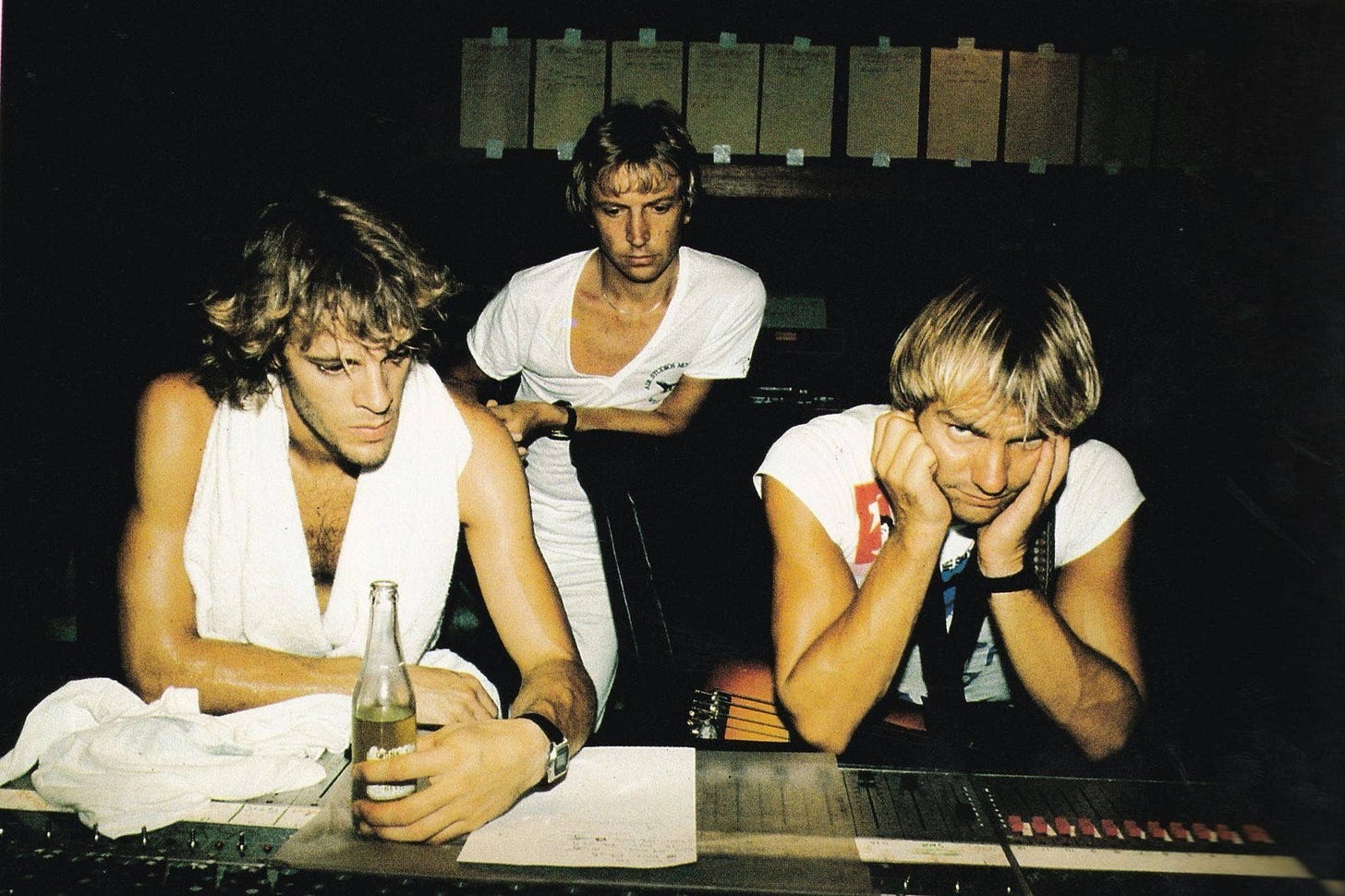

If you know anything about The Police, you’re well aware of the trio’s reputation for intra-band conflict.

And if anyone knows anything about that reputation, it’s producer Hugh Padgham. Over the course of two albums, he witnessed—and mediated—some legendarily furious disagreements, which resolved in the band’s biggest hits.

Asked about The Police’s squabbles, Padgham just laughs. “Well, that’s a whole interview itself,” he offers. “I think it’s well known that they had strong opinions in the studio.”

With the recent release of a massive, 84-song, six-disc version of the band’s 1983 magnum opus, Synchronicity, it’s worth reflecting on how often those arguments involved drum machines—and the under-discussed role of programmed rhythm in The Police’s history.

Normally, a half-dozen album’s worth of demos and alternate versions from a forty-year-old release would constitute an insufferable amount of padding. In this case, however, the multiple takes and outtakes tell an often-fascinating story about band dynamics. Hearing the demos that frontman Sting prepared with an Oberheim DMX drum machine, and the ways in which drummer Stewart Copeland and guitarist Andy Summers interpreted—or were allowed to interpret—those sketches is audible proof of something Sting said, years later, about why Synchronicity had to be the band’s last hurrah.

“To make a lifetime's career out of that tension wasn't possible,” he said. “We all had to back away from it.”

2.

Drum machines were not only part of the Police story from almost the very beginning—it was actually drummer Stewart Copeland who apparently first used them.

(He’s still interested: how can you help but smile at this recent video posted on his YouTube channel, where he asks drum machine mastermind Roger Linn, “What’s your problem with drummers? Why have you spent your life creating an electronic drummer?”)

In 1978, while The Police were still working their way up through the ranks of UK punk bands—in fact, during a period where Copeland would recall that the band was unfashionable and “actually kind of dead in the water”—he had written a sharp, snotty song called “Don’t Care.” Sting rejected the tune, reportedly feeling unable to connect with its lyrics.1 So Copeland decided to record the song himself, using the pseudonym Klark Kent.

However, “Don’t Care” started with a rhythmic bed provided by a pushbutton drum machine. At Surrey Sound Studio, with Police producer Nigel Gray manning the boards, Copeland recorded his “cheesy drum box” as a “glorified metronome,” which he would replace later with his own drums. Which drum machine it was, he doesn’t say, but he gives one clue in his autobiography Strange Things Happen: A Life with The Police, Polo, and Pygmies.

“This machine was designed to accompany lounge singers who are too cheap to hire a real drummer. It has preprogrammed rhythms, of which most are rumbas, sambas, and the like,” Copeland wrote. “But it does have ‘Pop 1’ and ‘Pop 2,’ which gives me two serviceable rhythms I can use.”

That’s an observation similar to one made by another famous drum machine user: Will Sergeant of Echo and the Bunnymen, who had, around the same time, purchased a Korg Minipops drum machine at Rushworth’s music store in Liverpool. The Minipops eventually—somewhat accidentally—won the nickname “Echo.” And it was a similarly limited drum machine, with only two rhythms—Rock 1 and Rock 2—that the Bunnymen found suitable.2

Copeland would record other Klark Kent songs using the same formula as “Don’t Care.” And years later, he would still recall hearing the results as a high point in a career filled with them. “There is no greater joy than this,” he wrote in Strange Things Happen. Listening to some instrumental tracks on a cassette in his car after a day of recording, Copeland recalled, “I don’t ever want to get home.”

You can hear Copeland’s drum machine-driven demos alongside the originals on the deluxe edition of Klark Kent, release in 2023. That includes the original version of “Don’t Care,” which became an unexpected Top 50 hit and got Copeland an invitation to perform on Top of the Pops.

He would invite Sting and Andy Summers (as well as his own music exec brother, Miles) with him to mime the song, wearing rubber masks. Even today, it’s surprising to realize that it was “Don’t Care”—and not a Police song—that got the threesome their first real national exposure.

Despite that memorable performance, however, “Don’t Care” stalled out on the charts. At that point, all parties turned their attention back to The Police.

It was the correct decision. The band’s debut single, “Roxanne,” would be re-released early in 1979, giving them a breakthrough Top 40 hit in America. From there, the group’s momentum continued to build until The Police became, for two or three years, the biggest act in the world.

3.

Drum machines would apparently not re-enter the picture for The Police until 1981. But when they did, they brought another significant hit—and significant controversy—with them.

“I can tell you exactly what happened,” says Hugh Padgham, on the subject of how “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” came to be.

At the time, the band was recording at George Martin’s AIR studios in Montserrat, and Padgham was taking over as producer for Nigel Gray, who’d overseen the first three Police LPs. “Sting recorded a demo of ‘Every Little Thing’ himself, in a studio in Montreal,” remembers Padgham. “And he had a Canadian musician named Jean Roussel, who played piano on the demo.”

In fact, the song predated The Police. Sting had written it in 1977, and had recorded an early version with producer Mike Howlett, who played with the Police lineup that year under the name Strontium 90.

That version—far slower, and largely percussionless—was given a far more expansive rethink at Le Studio in Montreal. Roussel, who’d previously played with Cat Stevens and Bob Marley, among others, added multiple piano tracks, as well as clavinet and Minimoog. The song, according to Roussel, was destined for Sting’s first solo album. But the singer ultimately brought the demo to The Police and Padgham in Montserrat.

“And we tried to recapture the feel of the demo,” recalls Padgham, “and we were just unable to duplicate it.”

This went beyond the usual frustration of copying the magic of a scratch recording, however. Demo or not, the song already sounded to all observers like a hit. And even years later, Summers was miffed at the contributions of Roussel, who was eventually flown to Montserrat. “(T)here wasn't room for him,” Summers told longtime Police chronicler Vic Garabini in 2000, in a freewheeling three-way interview for Revolver. “He must have played 12 piano parts on that song alone. And as the guitar player, I was saying, 'What the f*** is this? This is not the Police sound’.”

So Padgham remembers making a diplomatic proposal. “What we ended up doing—and this was my suggestion—was to just keep the demo, and have Stewart Copeland overdub the drums.”3

What Copeland was replacing was a drum track created by the Roland CR-78, otherwise known as the CompuRhythm. It was a groundbreaking device: the first widely available programmable drum machine. Later in that same year of 1981, it would appear on another album Padgham oversaw. That was Phil Collins’s Face Value, where it provided most of the percussion on “In the Air Tonight”—right up until Collins’s iconic midsong drum fill.

It’s unknown whose machine appeared on the “Every Little Thing” demo, although it seems likely to have been Sting’s: both he and Copeland would both eventually own one. However, you can still hear the original Le Studio version, with the CR-78, here:

Copeland would later recall that when presented with the demo, “we tried to make the song a Police song—which meant undoing all of Sting's arrangement. That was our basic policy anyway. Always has been. Throw out Sting's arrangement, keep his lyrics and the song.

“So we tried playing it slower than the demos, we tried my ‘rama-lama’ punk version. Andy tried turning the chords upside down. We spent more time on this song than on all the other songs put together. One morning, in a state of extreme grumpiness, I remember saying, ‘Okay, put up Sting's original demo and I'll show you how crummy it is.’ So Sting stood over me and waved me through all the changes. I did just one take, and that became the record.”

Here, Copeland was probably understating things. “Stewart’s performance was probably the greatest performance by a drummer that I’ve ever seen, in the studio,” enthuses Padgham—who has, remember, worked with Phil Collins, along with an army of the world’s top session pros. “The way he was able to replace that drum machine part on the demo, precisely. And then obviously, it ended up becoming quite a big hit as well.”

It was the band’s biggest hit thus far, in fact—a Number One in the U.K. and several other countries, and Number Three in the U.S. And despite the disagreements over the recording, Sting would later affirm Padgham’s praise.

“Stewart must be about the most amazing drummer—in the history of rock’n’roll,” he told The Independent in 1993. “He was a nightmare for me to play with, though.

“He and I have a different interpretation of where the beat is. I like to push the beat with the bass, be slightly ahead of it, which means I have to have a drummer to hold me down, the drummer has to be rock solid. But Stewart is the same as me—he likes to push the beat too, so we'd get faster and faster and be racing absurdly by the end.”

So perhaps it’s no surprise that Sting turned to drum machines as the rhythmic bed for his increasingly polished demos. In an interview with Jools Holland around the time of Ghost in the Machine, Sting demonstrated how he used a drum machine—called “Dennis”—to demo songs. In this case, he played a version of the old Police hit “Message in a Bottle” for Holland, using a boom box that apparently contained a cassette of programmed rhythms. Those patterns almost certainly came from the CR-78.

(However, “‘Dennis’ was known to be a moniker Sting affectionately gave to whatever drum machines he owned…which he normally used to record demos whenever a drummer wasn't available.”)

The CR-78’s claim on the name “Dennis” would be short-lived. Somewhere after the release of Ghost in the Machine, both Sting and Copeland each purchased a brand-new drum machine: the Oberheim DMX.

4.

The DMX, which debuted in late 1981, was Oberheim’s attempt to compete with the Linn LM-1, which had set the industry on its ear the previous year by using sampled drum sounds. Inventor Roger Linn had recorded his friend, session drummer Art Wood, to create a realistic-sounding drum machine that was quickly adopted by music industry pros.

The price of the LM-1 wasn’t cheap: $5,000. So Tom Oberheim enlisted a team that included a brilliant young engineer named Marcus Ryle to create another, more affordable, sampling drum machine. This one would get its sounds from Weather Report drummer Peter Erskine, and would retail for a hair under $3,000.

It would also become a component of a completely integrated system called the Oberheim Parallel Buss. The system, which also included a sequencer (the DSX) and synthesizer (the OB-X, and soon afterward, its successor, the OBXa), was a godsend in the days before MIDI, when getting machines to talk to each other was sometimes an impossible proposition.

The complete system cost $10,000, which Marcus Ryle notes made it targeted toward professional musicians. “Honestly,” he says, “there was no home recording yet.” But Sting was no hobbyist. Hugh Padgham recalls that Sting owned the Parallel Buss system, and it’s likely that it was used to make the demos for Synchronicity. (One of them even seems to reference one of the Parallel Buss components directly: a spare, hypnotic “OBX Version” of “O My God.”)

Copeland had also become a fan of the DMX, and also purchased the Parallel Buss system. In a 1983 interview with Ian Gilby in Home & Studio Recording, Copeland talked about scoring films—he’d just completed his first score, for Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish—and his own studio. “When I'm working in here,” Copeland revealed, “I'm much happier using drum boxes,” instead of real drums.

“I've been using the Oberheim DMX up till now, and that in my opinion has the best sound, the best bass drum and the best snare sound,” Copeland said.4 “The cymbals on all of them are crap, you need to overdub live cymbals for that. But the triggering and so on, where you put down a trigger track on channel 1 and then you can overdub anything you want just by syncing it back in, are great.

“In the old days you would have to record your drum box first, then put everything else on top of it. Now you record just four beats in a bar and a sync pulse track,” he added. “Once you've got the bass and the rest of the arrangement, you can put your drum fills around it instead of having to do all those first.”

But armed with the Parallel Buss system, Sting created intricate demos for Synchronicity. As was the case with “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic,” he presented fully realized song structures to his bandmates. And this time around, he wasn’t much interested in compromising his vision.

With the benefit of years of hindsight, Copeland came to terms with his bandmate’s inflexibility. He told The New York Post’s Chuck Arnold last year that making Synchronicity was “a very uncomfortable place — and we drove each other crazy. We now understand where all that tension came from. And in fact, given that understanding, I’m very grateful that we got as many as five albums out of Stingo, because by then…he had a very clear idea of how the arrangements should go.

“At first, it was collaboration. It became more and more compromise for him—and it got tougher and tougher for him to make those compromises,” added Copeland.

As Vic Garbarini would write in 2003, Copeland “should have seen that Synchronicity was really Sting's first solo album and that the dynamics of the group had shifted ages ago.”

Copeland also told The Guardian that while he and Summers only managed a song apiece on Synchronicity, it was tough to have hard feelings. “It wasn’t so much Sting that turned his nose up” at the duo’s songs “as that we all did. We’d all turn up with songs, but every time Sting pulled one out, they were such fucking good songs.”5

But it was one thing to concede the lion’s share of the songwriting to Sting. It was another to allow him control over the drums as well.

“The times when I came the closest to homicide, the times when it became absolutely critical that I choke the life out of this man,” joked Copeland to the Post, “were when he would come over to me and tell me something about the hi-hat.”

And that was, more or less, what happened with “Every Breath You Take.”

“That song in particular—the arguments just seemed to start immediately,” says Hugh Padgham with a sigh. “Every Breath You Take” would become not just The Police’s biggest and best-known hit, but also—according to BMI in 2019—the most played song in radio history. But it wouldn’t get there without a struggle.

“Sting brought in a demo,” remembers Padgham, “and he felt very strongly that he wanted the percussion to be very simple.” You can hear this for yourself on the demo, where the DMX provides a basic pattern containing just bass drum, side stick, and tambourine.

“And Stewart, being a world-class drummer, felt that he wanted the pattern to be somewhat more intricate,” continues Padgham. This argument can be traced out over several different takes available on the Super Deluxe version of Synchronicity; on one of them—the “Alternate Mix”—you can hear the sound of the eventual compromise.

“In the end, the bass drum from the DMX ended up on the recording,” says Padgham. “It was very insistent. And I think [Sting and I] really liked that insistency.” The “Alternate Mix” begins with this sound of the DMX bass drum, before Copeland’s kit comes in atop it.

“But Stewart ended up overdubbing the hi-hats, and the snare and toms. And he even overdubbed a big military bass drum on certain hits—that’s why you have that [bigger] sound,” Padgham adds. You can hear that bass drum, presumably, after Copeland’s crashing fill leading into the bridge.

In 2000, during the group’s three-way interview with Vic Garbarini, Copeland suggested that the controversy over the song wasn’t dead just yet.

“In my humble opinion, this is Sting's best song with the worst arrangement,” Copeland said. “I think Sting could have had any other group do this song and it would have been better than our version—except for Andy's brilliant guitar part. Basically, there's an utter lack of groove. It's a totally wasted opportunity for our band. Even though we made gazillions off of it, and it's the biggest hit we ever had, when I listen to this recording, I think 'God, what a bunch of assholes we were!’”

Taken in the context of this interview—in which the three Police gleefully insulted one another, and Garbarini—the criticism is relatively mild. However, there’s something worth considering in it—something that is revealed by listening to Sting’s demo of Synchronicity’s second U.S. single.

Despite its somber subject matter, “King of Pain” was a Number Three hit in the summer of 1983. This was a time when The Police’s only real rivals were a resurgent David Bowie, touring behind his comeback album Let’s Dance, and Michael Jackson, whose Thriller had just spun off its fifth hit single, “Human Nature,” and showed no signs of slowdown.

The familiar, filagreed arrangement of “King of Pain” that appears on Synchronicity matches its lyrics and gives the song appropriate gravitas. Like “Every Breath You Take,” it’s a brooding track that privileges painterly strokes over groove. That’s why it’s so surprising to hear how similar Sting’s demo sounds to the British synthpop that was all over the charts that summer.

In particular, listen to how Sting’s bassline locks in with the insistent, simple drum program of the DMX. The result is funky, and, despite the song’s sentiments, nearly playful—not just in a way reminiscent of, say, then-current hitmakers like Tears for Fears or China Crisis, but in a way that The Police themselves once had been.

We can probably agree that the band arrived at a more proper arrangement. Like most demos, this one lacks drama and dynamics: the only real concession there is the programmed ride cymbal added to goose the choruses. But this version of the familiar hit is a fascinating little window into the evolution of The Police, and of how its three strong personalities could complicate arrangements, as well as enhance them.

5.

By the time The Police reconvened in the studio for one final time in 1986, a lot of things had largely gone by the wayside. Any lingering goodwill between the three men, for starters. And standalone drum machines.

Copeland had broken his collarbone in a polo accident and couldn’t play his kit. So he and Sting were reduced to dueling over programmed rhythms provided by the Fairlight CMI and the Synclavier. “It was synthesizers at dawn in the studio,” wrote Chris Campion in the 2010 Police biography, Walking on the Moon.6 “Sting’s Synclavier was set up at one end, Stewart Copeland’s Fairlight at the other.”

It was a gentlemanly dispute—for a while, at least. Each waited for the other party to leave the studio, then replaced his rival’s drum patterns with his own programming. Eventually, Sting broke the deadlock in memorable fashion, approaching Copeland with “ a rose, a hug, and then—flick! a twelve-inch switchblade,” and the pair “got along famously the rest of the day.” Even the snare sound on “Don’t Stand So Close to Me ’86,” Copeland revealed, was a mix of the two samples he and Sting preferred.

But while the bandmates’ differences were patched over, the results of these sessions—downtempo remakes of “Don’t Stand” and “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da”—plodded along drearily, their drum programs absorbed into the heavily synthesized backgrounds. It had been one thing for Sting to channel Jung and Nabokov and Arthur Koestler; it was another to hear these formerly bouncy anthems drained of their lifeblood. “Instead of summoning their creative energies at their instruments," wrote Vic Garbarini in Guitar World, “the Police have been reduced to punching out rhythms on a keyboard.”

The remade “Don’t Stand” stalled outside the U.S. Top 40, and “De Do Do Do” wouldn’t even see release for nearly two decades. It certainly wasn’t the way Police fans would have hoped to hear their heroes depart the stage, their symbolic “passing of the torch” to U2 at that summer’s Amnesty International tour notwithstanding.

The switchblade moment, and the detente over snare sounds, had not, Vic Garbarini said, really resolved anything—except this. “Sting, Stewart and Andy realize their business has been concluded. The Police, and the animosity that marred much of their existence, are finished.”

6.

Of course, that wasn’t truly the end of the story. The Police would regroup to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003, and again for a lucrative world tour in 2007 and 2008. Could it happen once more? It seems unlikely, which is why the Super Deluxe re-release of Synchronicity bears such scrutiny. This may be the only new evidence forthcoming about what made The Police such a truly great—and truly maddening—band.

Whether Synchronicity truly was Sting’s first solo album, as well as The Police’s last, drum machines played a big part in bringing it to life. And throughout the band’s five- or six-year reign as pop Olympians, drum machines often provided a programmed backbeat—and a ready source of controversy.

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com. And this post has you interested in snagging a copy of the Super Deluxe version of Synchronicity—six CDs; four LPs—then visit thepolice.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.

Which still seems a bit surprising. Sting couldn’t get his head around a lyric that goes, in part, “I am the coolest thing that ever hit town”? Really?

In fact, if you listen to Klark Kent’s lone album, released in 1980, you may be surprised that none of these songs made the cut for The Police. Several of them are punchy, catchy numbers that certainly aren’t a million miles from the pop-punky reggae the band was essaying in those days. And certainly a few are superior to some Police album tracks of this period. But as the re-release of Synchronicity suggests, The Police had a habit of leaving some superior tracks in the can.

So was Copeland’s drum machine a Minipops as well? Perhaps; it may be that he’s remembering the “Rock” presets as “Pop” instead.

In true Police style, both Sting and Copeland would later claim that recording drums over the demo of “Every Little Thing” was their idea.

The legend of the DMX was that its sampled sounds were punchier than those of the Linn LM-1 and LinnDrum. “DMX drums, they certainly had an attitude,” says Jimmy Bralower, the acknowledged “King” of drum programmers. “The Linn really didn’t.” In Chapter 16 of Dancing to the Drum Machine, Marcus Ryle reveals how the use of filters affected the sampled sounds of the DMX.

However, you can certainly make the case that both Summers and Copeland brought in material for Synchronicity that ought to have been more seriously considered. Summers’s loping “Goodbye Tomorrow” might have been an easier fit for the album than his Oedipus-meets-Captain Beefheart-style “Mother,” while Copeland’s “I’m Blind” is the equal of the slight-but-charming Cold War love song “Miss Gradenko.”

But the real missed opportunity came with one of Summers’s finest offerings. “Once Upon a Daydream” failed to make the cut for both Ghost in the Machine and Synchronicity. The demo version here is a gem, in spite of Sting’s morbid fairy tale lyrics: the chord progression is haunting enough to imagine the song as a could-have-been hit.

"I love it. It's a set of chords Andy came up with and I wrote some lyrics to them by the swimming pool in Montserrat,” recalled Sting. “It's very dark, but that was the Ghost period—pretty intense."

Copeland’s recollection, meanwhile, was typically wry: ”Most people would lounge and bask in the sun by a swimming pool, but Sting would create a cloud around himself and stare grimly at the horizon while he organised his dark thoughts into beautiful music."

Campion’s pungent biography has come in for occasional criticism from fans who think he’s too hard on The Police—and their manager, Miles Copeland. I lean toward believing it’s not only the kind of warts-and-all bio any band of substance ought to warrant, but that it’s impossible to tell the group’s story without challenging some of the frequent mythologizing.