The Power and the Glory

How the biggest of the Big Eighties albums changed the game—one drum hit at a time.

Nearly halfway through the year, have you had your fill of music pieces that begin “it was 40 years ago today”?

Probably. And that’s because 1985 was such a remarkable 12 months in the lexicon of pop music—and not merely for the inevitable Live Aid anniversaries that will be observed next month. (I hereby reserve my right to write one myself: check this space.)

With that caveat established, let’s travel back to the spring of 1985, and the release of an album that changed popular music in ways that, even now, we don’t fully appreciate.

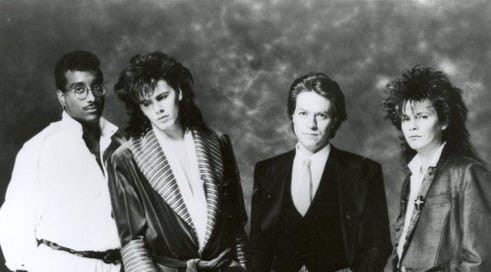

When The Power Station released its debut LP on March 25, it was greeted with what we can best describe as critical skepticism. Two-fifths of Duran Duran were involved—bassist John Taylor, and guitarist Andy Taylor, along with. Chic drummer Tony Thompson and blue-eyes soul vocalist Robert Palmer.

The Duran backlash, at the height of their fame, was considerable: How dare these untalented limeys indulge in a side project? I memorized the Trouser Press review, which, at age 16, I found a little heartbreaking:

On paper, a promising idea — especially in light of the Durannies’ funk pretensions and Simon Le Bon’s vocal inadequacies—but, on vinyl, a miserable, boring explosion of overbearing drums pounding (you thought the drums were mixed high on Let’s Dance?) through tuneless, formless “songs.” While the slickly functional dance-funk is just minor on the softer numbers, the ultimate realization of the concept, “Some Like It Hot,” offers a numbingly industrial take on electro-funk made truly execrable by Palmer’s contemptible singing. But that’s nothing compared to the excruciating jam/destruction of Marc Bolan’s “Bang a Gong (Get It On),” matching an appalling lack of originality with utter disdain for (and desecration of) the song’s melody, tempo and boppy charm.1

(In those impressionable days, I believed that The Critics™ were unimpeachable arbiters of what truly counted in music. A bad review of a band I loved in Rolling Stone felt really personal, somehow. I assumed these writers knew far more than I did, and I took their words deeply to heart, even when I profoundly disagreed with them, as in this instance. But something punk icon Henry Rollins told me when I became a writer myself has always stuck. “Everyone—from us to Bon Jovi—works really hard on making records,” Rollins growled. It was a great reminder to trust my own judgement above what any critic had to say—and to check myself before unleashing some witty bon mot about an artist I felt had fallen short of the mark.)

I convinced my long-suffering mother to take me and my younger brother to see The Power Station that summer of 1985, in not-nearly-nearby Richfield, Ohio. Even though I was hoping for Go West as the opening act (we got OMD, on the verge of their U.S. breakthrough, instead), and even though we also got journeyman singer Michael Des Barres, late of Chequered Past, instead of the far more urbane Robert Palmer, it was still thrilling to actually see the group in person, and hear the echoing racket they made.

Years later, the critical opprobrium about The Power Station had not abated entirely. But there was at least an acknowledgement that they had accomplished something remarkable—and, perhaps, noteworthy.

From a 2015 piece by Simon Price in The Quietus, which compared The Power Station to the other Duran Duran side project of this time, Arcadia:

But everything anyone needs to know about The Power Station is in that opening track, the debut single. Fire up the twelve inch, turn it up to 11. Your septum hurts, just listening to it. “Some Like It Hot” feels like being slapped by Tony Montana then skullfucked by Patrick Bateman. The Power Station are the high water mark of the BIGNESS of the Eighties: big dreams, big noises, big budgets, bigger shoulder pads, biggest drug habits. They’re musical Ozymandias. Look upon their mighty works, ye feeble peons, and despair.

Today, most of us old enough to remember recall that The Power Station produced a Top 10 album and two Top 10 singles—“Some Like It Hot” and a cover of T. Rex’s “Get It On (Bang a Gong).” That they played at Live Aid (about a month before I saw them in Richfield).

That they were a springboard for Robert Palmer’s greatest solo success with songs like “Addicted to Love” (he later argued that it was the other way round). That eventually, John Taylor returned to Duran Duran and Andy Taylor went solo.

But what’s harder to remember, unless you were alive and following pop music at this time, is the effect that this album had on pop music for the rest of the decade, at least.

Specifically, the sound of its drums. The massive drum sounds that Tony Thompson contributed to David Bowie’s Let’s Dance (1983) and Madonna’s Like a Virgin (1984)—both productions overseen by Thompson’s Chic bandmate, Nile Rodgers—only hinted at the sound that the Power Station LP would unleash.

The only previous sound comparable to Thompson’s kit was the late John Bonham’s drumming in Led Zeppelin, the gold standard in “big drums” to that point. Bonham’s larger-than-life drums were so revered that when sampling entered pop music at about this time, it was his sounds that early samplers thought to grab.2 It was hardly an accident that when Led Zeppelin reformed for Live Aid that summer, it was Tony Thompson that they approached to sit on the vacant drum throne.3

But it was on The Power Station that Thompson reached the pinnacle of Eighties drumming: a sound so huge that it seemed almost impossible. This was in part the result of Thompson’s own physicality: he used his long arms and legs to generate incredible amounts of force that sometimes blew out studio microphones. Yet it was also the work of Jason Corsaro, an engineer at The Power Station, the New York studio from which the band took its name.

Corsaro built on the work of legendary engineer and mixer Bob Clearmountain, who’d done some of his finest work at The Power Station. As just one example, Clearmountain recorded Tony Thompson’s playing on Let’s Dance, which, at the time, seemed to skirt the outer limit of big drum sounds.

Sometimes Clearmountain worked at The Power Station with drum programmer Jimmy Bralower, known as “The King” of drum machines.

“The Power Station rooms were so definitive,” Bralower told me. “Studio C was where the Duran stuff happened, and Madonna. There’s a certain sound in that room. Then Studio A was the big rock room. That’s where Billy Squier was done, and also Bruce Springsteen’s “Hungry Heart.” A lot of big rock records from that era were done in Studio A. You couldn’t help but get a great sound in that room. It was just built for speed.”

On the 1984 Hall and Oates single “Adult Education,” Clearmountain and Bralower teamed up for a virtual master class in Eighties drum recording. “It’s all drum machine until the end, then live drums take over,” Bralower recalled. Hall and Oates “didn’t give a shit if it was a drum machine or a live drummer. All they knew was that this worked.”

But Jason Corsaro was determined to extract an even larger sound from live drums—especially the already massive hits of Tony Thompson.

There has already been hints at what this might sound like on Chic’s “You Are Beautiful,” a 1983 European single that Corsaro engineered. While the rhythm is, like “Adult Education,” a mixture of programmed and live percussion, Thompson’s rumbling fills—especially the ones that occur during the breakdown (around 2:40)—already sound like they’re ready to burst beyond the confines of the track.

Bill Laswell, the bassist and producer who helped oversee everything from Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” to Public Image Limited’s Album during this era, goes so far as to claim that Corsaro’s drum recordings “replaced the drum machine.”

From Dancing to the Drum Machine:

To maximize (Thompson’s) natural ability, Corsaro performed an intricate series of punch-ins to Thompson’s drum tracks. He added precise dollops of reverb that threaded a tiny needle: the drums were enormous, yet each strike remained distinct.

Laswell recalls vividly his first meeting with Corsaro.

“I was waiting in reception at the Power Station. And two guys came in carrying him, one on each side. He looked like he was asleep. And I went to the receptionist and said, “Is that Jason Corsaro?” She said yes, and I said, “Well, I guess I’ll come back tomorrow, because it looks like he’s going home.” And she said, “Oh, no— he’s just arrived to work.” Jason was insanely into drugs and alcohol. But that began this long relationship.”

Whether Corsaro’s work did, in fact, replace drum machines, it’s inarguable that The Power Station played a part in a sort of countermovement that occurred during the second half of the Eighties. Once again, from DTTDM:

As the 1980s waned, there was an inevitable backlash against the sound and aesthetic of drum machines. It took many forms, including a resurgence in hard rock and “authentic” musical forms. at helped drive the success of mainstream acts like Bon Jovi, Guns N’ Roses, and a second wave of hair metal bands who dominated MTV.

The irony was that many of these artists were using drum machines and electronic sounds. A common practice was attaching triggers to a drum kit to generate electronic sounds that would become a major part of the final mix.

“At a certain point in my career, I wanted a real drummer. Because I had a batch of samples and sounds that were just monstrous,” says producer and engineer Mark S. Berry. “So you drum it, we’ll get the triggers right, and I’ll put the sound on afterwards. We put a little bit of the real drum in there, so we have the sonic quality of a sample, but so you can still hear the foot pounding the bass drum.”

(Here’s one of those productions you may remember:)

Beginning in the late 1980s, drummer David Frangioni became one of the industry’s go-to technologists. An early adopter of drum triggering, especially in the live setting, Frangioni worked with artists like Aerosmith and Ozzy Osbourne to develop the right blend of acoustic and electronic sounds.

Frangioni, an author and entrepreneur who’s also the CEO of Modern Drummer magazine, admits that “early on, triggering was a huge challenge.” He became a fan of the Dynacord ADD-One drum synthesizer and sampler, although he notes, “I would just look at the project, the drummer, and figure out what the right triggers were. I did all my homework ahead of time.”

One common technique—especially on metal albums, where huge drum sounds were a requirement—involved a sort of after-the-fact triggering. “The drums would get recorded, and then the producer—and a guy like me—would trigger the sounds to the tape. And that would be added to the blend that would become the final sound,” Frangioni recalls. “That was actually more commonplace at that time than triggering while the drummer was playing.

“And of course, that got your drums done a lot faster. The drummer could play exactly as he wanted, and then it was all in the hands of the producer and the mix engineer and the technologist, which was my main role.”

One of the masters of this technique, Frangioni adds, was Beau Hill, the producer of such successful metal bands as Ratt, Winger, and Warrant. “Beau was known for his great ability to take drum sounds after they were recorded, and hear how they were sitting in the track, and then gure out how to trigger the sounds,” Frangioni recalls.

There are other markers of this shift. You can hear early indicators, for example, in Pat Benatar’s 1985 single “Sex as a Weapon,” where drummer Myron Grombacher is pushed to the top of the mix and gives a speaker-rattling performance.4

Here’s the remix by Steve Thompson—one of the best of this era.

Toward the end of 1985, “She Sells Sanctuary,” by the British quartet The Cult, became a club hit in the U.S. Hair metal was one thing; but, like The Power Station, The Cult helped make straight-ahead hard rock something even alternative audiences could embrace.

And a year later, the band teamed with producer Rick Rubin—who’d been enamored of the Drumulator’s Rock Drums 1 chips in his work with The Beastie Boys—to create a what-if-AC/DC-met-Led-Zep-album called Electric.

When others tried to copy Corsaro’s laser-focused drum recordings, however, the result was less and less and space. Toward the end of the Eighties, drum sounds got so huge, as David Bowie’s guitarist Carlos Alomar told me, “you have a three-piece band that sounds so fuckin’ huge that there’s no space to put anything else!”

Alomar, who did his share of recording at The Power Station, observed that “music needs holes. Silence in music is just as powerful as the beat.”

How did that silence return to music? One way was through sampling, which allowed even novice producers access to drum sounds of a bygone age. James Brown’s “Funky Drummer,” Clyde Stubblefield, was undoubtedly a master behind the kit. But something few remarked upon at the time was that the much smaller drum sounds of the Sixties and Seventies naturally allowed the space—the “holes” Alomar mentions—needed for music to swing.

Sometimes that space was partially filled by the flams and ghost notes that would become a common feature of sampled music, from Golden Age hip hop to Madchester to trip-hop to electronica. Regardless, across the board, as drum sounds shrank, funk returned. That, however, is a story for a future installment.

Tony Thompson died tragically young, from kidney cancer, at age 48 in 2003. Of all the “I’m glad I saw them while they were still living” moments in my concert-going career, getting to witness him back in 1985, at the height of his Power Station power, is near the top. Jason Corsaro, meanwhile, also passed away from cancer far too soon, in 2017.

Together, they not only changed the sound of popular music: they took it to an absolute limit. To say that it wasn’t possible to go any further than the work you did is some kind of compliment. The power—and, let’s be honest, the glory—of The Power Station is a frontier of Big Music we’re unlikely to see crossed again.

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

For those who have been kind enough to ask, yes, there is a follow-up to Dancing to the Drum Machine in the works. I’m working on it in fits and starts, and hoping for a 2026 release. Stay tuned for updates!

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple Books, and other online retailers.

As a teenager, I was convinced that this review meant that Marc Bolan—whom I knew then only vaguely, in relation to David Bowie—would have hated this version of his song, and fretted about what this disapproval might mean in the larger scheme of things. Years and years later, writing a magazine piece about the reissue of T. Rex’s Electric Warrior, I found myself talking to a medium who claimed to be able to summon the spirit of Bolan. One of my few professional regrets is that I failed to ask her—sorry, Bolan—what he thought of The Power Station’s “desecration” of “Bang a Gong".”

Most notably—and allegedly—as the source of Digidrums’ famous “Rock Drums 1” chips for the Drumulator. Digidrums co-founder Evan Brooks neither confirms nor denies this rumor.

It was reportedly only Thompson’s involvement in a serious car accident in the summer of 1986 that prevented a more serious Led Zep reunion from taking place.

Perhaps not coincidentally, this song was written by Tom Kelly and Billy Steinberg, the team responsible for Madonna’s “Like a Virgin”—a showcase for Tony Thompson and Jason Corsaro.