When you talk about great session men of the 1980s, you’re speaking not just about players with musical chops. You’re inevitably talking about musicians with technical chops, as well: guys who were as much great scientists as great players.

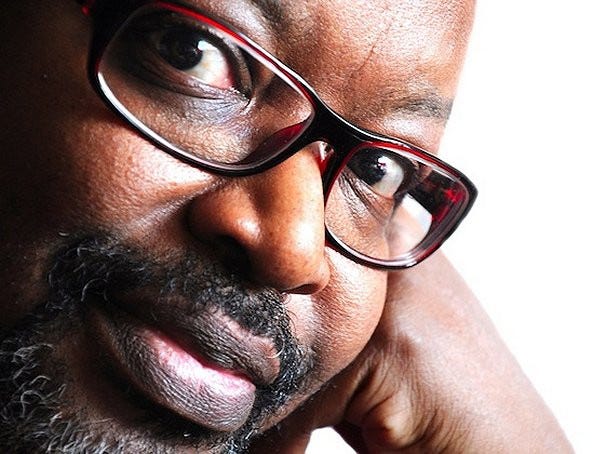

The honor roll of these largely unsung Eighties geniuses is long, but it has to include Wally Badarou. The Paris-born keyboardist played a major role in some of the most formative songs of the decade. Actually, we need to start that clock running in 1979, when his first solo album, Back to Scales appeared—and when he contributed to Robin Scott’s massive global hit “Pop Muzik,” a song which anticipated many of the trends of the next decade.

Badarou became a member of the Compass Point All-Stars, a collective that included some of the top studio pros of the day. The house band at Compass Point studios in Nassau, the All-Stars included Badarou’s longtime pal Sly Dunbar on drums, and Dunbar’s rhythm section partner Robbie Shakespeare on bass)—as well as guitarist Mikey Chung, percussionist Uziah "Sticky" Thompson, and guitarist Barry Reynolds. Members of this group would contribute to seminal LPs from Grace Jones, Tom Tom Club, Black Uhuru, Mick Jagger, and Jimmy Cliff.

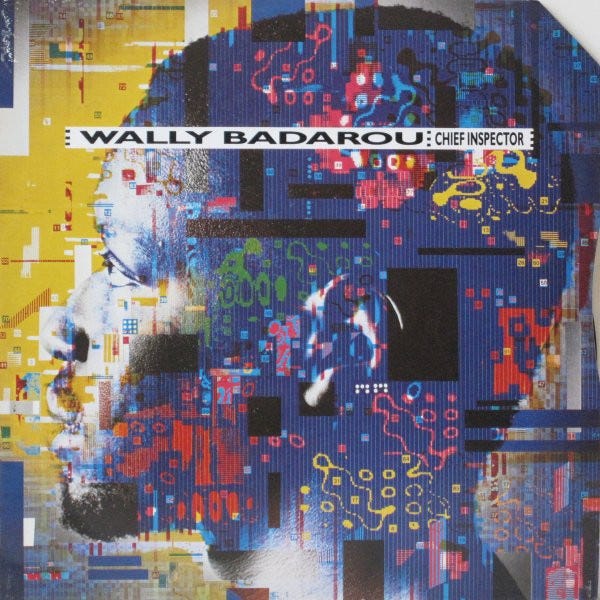

Badarou himself would go on to oversee hit albums from the British funk act Level 42, including 1985’s World Machine, which included the transatlantic Top 10 hit Something About You.” And his solo career produced such influential singles as “Chief Inspector” and “Mambo” (later sampled by Massive Attack) from his 1984 album Echoes.

In honor of his 68th birthday, which he’ll be celebrating later this month, here’s a conversation with Wally Badarou about his illustrious musical past, and the present-day implications of drum machines and other recording technology.

One question I have been asking everyone for this book is whether they remember the first time they ever heard a drum machine—whether it was on a record, as part of someone’s home organ setup, in a music store, etc. Do you recall the first time you encountered one?

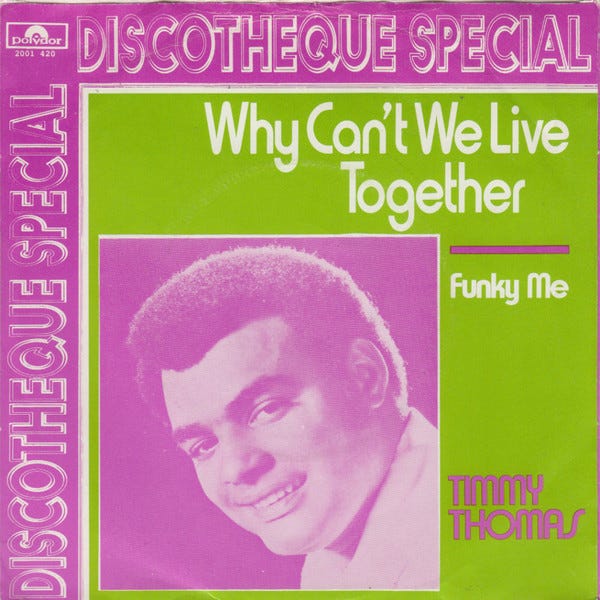

It was a built-in “rhythm box” in a home organ at a friend’s house, back in 1971. The first time I heard it, without realizing it was an organ drum box, was on Timmy Thomas's “Why Can’t We Live Together” hit.

I wondered as well about the first drum machine you might have owned, and why you chose it?

It was a Roland CR-78 CompuRhythm. I simply did not know any better, and could afford it.

[A drum machine] never pretended to replace a drum kit in my mind, anyway. I took it for what it was: a rhythm box. I learned to like it and to integrate it in my compositions. After all, if you write for a violin, you write with its sound in head. So I had no problem with that.

—Keyboardist Wally Badarou

Your first keyboard was a Korg 800-DV. Some folks in those days were able to use keyboards like this one to generate drum and percussion sounds, and I wondered if you did similar experiments?

For sure, extensively, on all of my demos back then.

One reason for the previous question is that you mention, in “The Barclay Era” section of your website, that you augmented your setup with other Korg devices. But no rhythm machine is mentioned, so I wondered if you were programming percussion from a keyboard?

The 800-DV—as well as its simpler version, the MiniKorg-700, and the Polyphonic Ensemble PE1000. All came with a very handy “Traveler” Hi- and Lo-cutoff double-fader that allowed real-time snare and bass drum emulation in one take—quite useful when recordable track number was an issue. That was before I could afford the Roland CR-78.

I’ve certainly talked to people who recall that drum machines were greeted with a fair amount of suspicion in the early days. Some saw them as little better than toys; some drummers feared the machines would take their jobs. Do you remember encountering resistance to drum machines from musicians, producers, or others involved with music?

Yes, I did encounter quite some resistance—which I always thought was legitimate. The same went for the synths as a whole, especially the string machines. Then the same applied to the samplers, and then, and then…Evolution always encountered resistance and before us, the church organ and the pianoforte were no exception. Jobs were at stake, inevitably.

But I did also encounter brilliant drum players who did embrace the technology fully, such as Sly Dunbar.

Your 1979 solo album Back to Scales Tonight sounds like it has some rhythm programming on it. Could you talk about the machines you used on this record?

The Roland CR-78 exclusively—for I owned it, so I knew how to use it. It didn’t have the programmability one could find on later machines, but simply put, I simply did not know any better anyway, so I had no choice but to accommodate with the flexibility I had been offered.

It never pretended to replace a drum kit in my mind, anyway. I took it for what it was: a rhythm box. I learned to like it and to integrate it in my compositions. After all, if you write for a violin, you write with its sound in head. So I had no problem with that.

The only problem I had was its inability to offer precise tempo setting. It took me a good deal of valuable, and expensive, time to replicate the tempo I had on my demo cassettes later in the recording studio. Plus, I could be misled by the speed of the cassette player, which yielded in Back To Scales Tonight being substantially faster than the demos, much regrettably.

The M and Level 42 records you played on featured the drummer Phil Gould. Could you talk about the role of drum programming on those records—if in fact there was any drum programming?

The only drum programming we kept was Level 42’s “World Machine,” the song, for I had it all programmed on a Linn 9000, along with the Lexicon 200 reverb unit I used for the polyryhtmic effect. The band just loved the sound of it on the demo, so we deliberately went for it in the studio. Other than that, we never used drum machines, as far as I can recall.

Similarly, the work you did with the Compass Point All Stars not only included a legendary drummer, Sly Dunbar, but one who has a reputation for programming drums as well. Did you end up doing any drum programming on those projects, or did Sly handle that himself? I’m thinking especially of Black Uhuru’s Chill Out, on which I assume Sly was in charge of the percussion.

Not only did Sly do it himself, but he was, and still remains, highly excited by the technology. He always owned and mastered them, no problem, and we could spend time, him and I, discussing their values and sounds.

We even spent time together in New York’s Manny’s and Sam Ash stores, devising about which one to pick next—after his affectionate Oberheim DMX machine. You can bet Sly never needed assistance on that: he was a master in the field.

By this point in the Eighties, most studios had a standalone drum machine or two that were standard equipment. I assume this was true at Compass Point, and I wondered what that machine/those machines might have been at this time?

Under Sly’s adamant choice, Compass Point ended up having its own Oberheim DMX machine.

One of the first Compass Point albums from this era that sounds like it might use a drum machine is Gwen Guthrie’s first album. Did you do any drum programming on this album? And if so, do you recall what machine was used? It’s also possible that only the snare sound was augmented — some songs sound like they might feature a device like the Clapper or Syndrum on the snare, combined with live drums.

That was Sly’s Syndrum system solely, mainly for the snare, the toms and the effects—never for the bass drum, as far as I can recall. The same applied to Grace Jones “Pull Up To The Bumper,” as well as many of the intros on all albums of the times.

One reason for asking this question is that I read in your biography that, at some point, you acquired the Oberheim integrated system, which featured the DMX drum machine. I wondered if you recalled when you made this switch, and what your recollections of the DMX in particular might be?

Funny enough, my Oberheim system had it all, OB-8 and DSX sequencer, but lacked just one piece: the DMX. I went for the Linn machines instead, right away. At Compass Point, Sly was the Oberheim guy; I was the Linn.

I’m curious as well because there is a song or two on Mick Jagger’s 1985 album She’s the Boss—“Running Out of Luck,” most notably—that sounds like it uses a drum machine. I asked Bill Laswell about this, and he couldn't recall who might have programmed it, so I thought I would ask you this same question!

Well, I surely did not. The only person eligible for that could only be Sly, but I was not around when the “Running Out Of Luck” backing tracks were recorded, so I can’t confirm. I only provided Synclavier tracks to Mick Jagger’s album, from within my private recording room.

Your 1984 album Echoes seems to feature a lot of drum machines (or at least, programmed percussion). In an interview I read, you talked about using a LinnDrum to come up with the rhythm for “Mambo,” and mentioned that it was derived from the rhythm of your song “Chief Inspector.”

Which Linn were you using at the time—the LinnDrum, or the Linn 9000? And did you use that same machine on the rest of Echoes?

I did it all on my LinnDrum machine, used extensively and exclusively throughout the whole of the album. After hearing Steve Winwood’s LM-1 on his Arc Of A Diver album, I thought I should go the Linn’s way.

The LinnDrum had just got released—more modern and quite less cumbersome—so I decided to acquire one, during my stay in New York while we were recording Marianne Faithfull’s A Child’s Adventure album.

I remember learning and practicing the LinnDrum back in my hotel room, storing improvised presets and patterns which eventually became those of “Mambo”, “Hi-Life” and “Chief Inspector.”

(A)t the end of the day, I could look at myself in the mirror and say: this composition is fully mine, from the main melody down to the slightest hi-hat struck. Just like the synths, the drum machine made me a full music composer.

—Wally Badarou

I saw on your website that the Linn 9000 is apparently the only standalone drum machine that you have kept. I wondered why you retained that machine, and whether you had the same difficulties with it—software problems, breaking down frequently, general undependability—that so many other users seem to have experienced?

I kept it for as long as I had valuable compositions within—drums and MIDI. It also had a distinct timing, which I always loved. And yes, just like any sophisticated computerized system, it had problems, which you could easily live with once you understood the value of constant backup—a habit that owning and operating a Synclavier system down in hurricane-ridden Nassau, in the Bahamas, swiftly taught me to adopt.

I ditched my beloved Linn 9000 only recently, for ergonomic reasons in my current setup.

You also used the Synclavier, which—like the Fairlight and the PPG Wave—was also used by some artists to get drum sounds. Did you use it for this purpose?

No I never did, for two reasons: First, I always preferred the inherent timing of the Linn machines, and would rather sync the Synclavier to them. Second, sampling time on the Synclavier could cost you an arm and a leg, if what you wanted was to replace a drummer with all the human feel and subtleties. That never was my idea: if I wanted a drummer, there were plenty I could have easily chosen from, you can bet!

I always went for the drum machine for what it was: a robotic player which inherent stiffness I felt I could compensate [for] with my writing, my performing and my mixing. Some stiffness could still remain despite the hard work put into it, but at the end of the day, I could look at myself in the mirror and say: this composition is fully mine, from the main melody down to the slightest hi-hat struck. Just like the synths, the drum machine made me a full music composer, the way I [see] it to this day.

I really first discovered your music through the inclusion of “Keys” on the 1986 Good to Go soundtrack. I always wondered how this song came to be selected for this particular soundtrack?

I believe Chris Blackwell chose it. No drum machine in it, though.

Is there any drum programming on the 1986 Fela album you produced, Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense? I ask in part because I know it was recorded in a very short timespan, so I wondered if any pre-programming took place?

Absolutely no electronics nor programming whatsoever. It was a very short recording and mixing project, simply because it was like a real 60 piece-symphonic orchestra, fully rehearsed beforehand, [with] songs that were so long there was simply no time for second or third takes.

The three songs were all first takes. There was nothing much we could do mixing-wise either, everything being sonically, stereo, and spectrally set at recording time. So once the musicians, the choir and the mics had been properly set and placed, it all went like a breeze.

There is a quote from your biography that reads, “To the aviation lover I am, the studio has appeared like the cockpit of a virtual aircraft that would fly over the sonic landscapes of a fantasy world. Ever since, and regardless of its inevitable 'virtualisation', it has remained that painter workshop where, stroke after stroke (track per track), I sense, build and finalise the artwork that you get.”

I wondered, overall, what role drum machines played in that visualization during the 1980s?

The same as it does to this date: synthesizer and drum machines remain at the core of my creativity. I tend to use drum samplers, either externally such as Emu’s beloved Procussion module, or internally with Kontakt, or a combination of both nowadays. But the principle remains the same: I want to be held responsible for each and every sound and nuance you hear.

At some point before the end of the 1980s, drum machines mostly get folded into sampling workstations. And computer recording—which you’d already started doing—was starting to become more feasible. At what point did you make the transition away from hardware to software?

At the turn of the century, when computers started to be powerful enough—and hard drives affordably big enough—to allow me to do the switch. My studio is all virtual nowadays, and I'm only keeping one rack of hardware for vintage gear I cannot find virtual versions of.

Today, of course, you can get any drum machine sound you want via plug-in. There are still some people who swear by the old standalone units, however, for various reasons—sound quality, timing, the tactile experience). You have been pretty open about the benefits of computer recording, but I wondered about your take on this hardware versus software question, regarding drum machines specifically. Is there still a place for the standalone drum machine?

As “electronic” as I may have looked, I have used machines only because they allowed me to be the full composer and performer I’ve always aimed to be. I never was a machine freak, per se. My keeping some of my machines [for] quite a long period never had anything to do with nostalgia: it was mostly due to either them remaining an integral part of my ongoing creativity, or the lack of time or means to transfer them into virtual domain.

Sure enough, each hardware machine has its own sound and feel, but interestingly enough, the writing and the performing always came first in my eyes. I am one to believe you can give me anything, and I will make music with it, regardless of the quality or the flaws.

I truly mean it.

Tune in for more full interviews with the pioneers of drum machines, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.