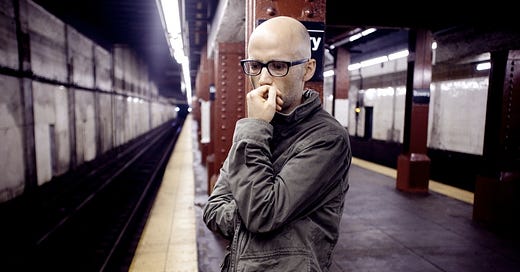

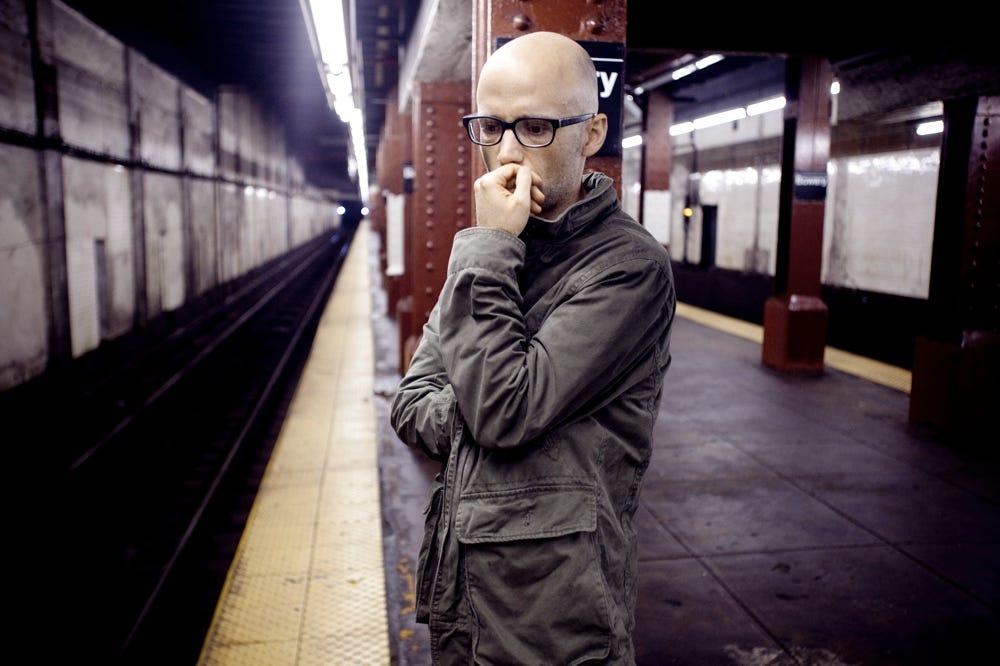

Rhythms Remembered: Moby's Drum Machine-Filled Life

Moby recalls the drum machines he left behind, and the ones that inspire him still

When it comes to drum machines, you might consider Moby The Man Who Sold the World.

At one time, Moby boasted the world’s largest collection of rhythm boxes, including such rare pieces as the tape loop-based Chamberlain Rhythmate and the Wurlitzer Side Man, as well as smaller curios like the PAiA Drummer Boy. But nearly a decade ago, he had an epiphany.

“I had two very big storage lockers filled with equipment and I had—I mean, just so much stuff that I'd accumulated over the years of touring, of buying equipment,” Moby recalled from his Los Angeles home. “And the truth is, I used approximately 1 percent of it.”

That included not just his drum machines, but a collection of vintage synths, as well as vinyl records he’d accumulated throughout his life. And the musician, DJ, activist, and author realized it was finally time to let it all go.

“Like, I had a Jupiter 6, two Juno 106es, a bunch of MOOGs, a beautiful—I think it was either a Rhodes or a Wurlitzer electric piano. Just so much stuff, and it never got used,” said Moby. “And it felt like such a shame. Why did I have all this wonderful stuff sitting in storage, collecting dust? Same thing with my records. I had thousands of records that simply never got played.

“And I just thought, you know what? If I sell my drum machines, if I sell my equipment, if I sell my records, I can generate money for charity, and the people I sell them to will actually use them, or will actually listen to the vinyl.

It will mean way more to someone who's buying one special drum machine, for them to own it than for me to have three or four hundred of them sitting in a storage locker, collecting dust.”

So in the fall of 2018, Moby held a massive sale through the online gear site reverb.com, asking buyers to “please take care of my babies.” He donated the proceeds to the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. But that divestment didn’t lessen his love of drum machines a bit.

In this Bonus Beats conversation from the autumn of 2020, Moby spoke about his earliest drum machine experiences, the most overrated drum machine of all time, and—in an experience I was happy to know we shared—the late, great Synsonics drum kit, among other subjects.

I wanted to say, first of all, not just thanks for doing this, but also, how much I enjoyed reading your memoir, Porcelain. There’s a really beautiful passage in the prologue where you talk about hearing the song “Love Hangover,” and realizing that this futuristic sound might be able to transport you away from your everyday reality.

So I'm wondering: do you remember the first time you ever heard a drum machine, on a record that that gave you any kind of similar feeling?

Yeah. It's an interesting question. I'm assuming that the first time I would have—well, the first time I heard a drum machine, I don't think I was aware that it was a drum machine. And it might be one of the first pop music uses of a drum machine.

I know a lot of people cite Sly and the Family Stone. But I actually think that “The Boxer” by Simon and Garfunkel is based around a drum machine. If you go back and listen to it, there's the underlying rhythm. So I think that, oddly enough, Simon and Garfunkel were the accidental pioneers of drum machines in pop music.

I've probably heard that record thousands of times, and now I gotta go back and listen again.

Yeah. Go back and listen. It sure sounds like a drum machine to me.

(Editor’s note: I made every effort to chase down this story, including contacting Columbia producer Roy Halee. I was not able to confirm the presence of a drum machine, but here’s a nice piece about the recording of “The Boxer” that highlights some of the track’s innovations, including the famous “exploding snare” sound played by legendary drummer Hal Blaine.)

But I think apart from that, it might have been at the beginning of the disco era. I think that—I could be mistaken, but I feel like “Rock Your Baby” by George McCrae is also based around a drum machine pattern. And that is cited as being one of the very first disco records.

So it's probably, you know, being in the car with my mom, listening to AM radio in Connecticut in the early Seventies, and hearing “Rock Your Baby” by George McCrae.

In the very next chapter in the book, you describe your abandoned factory studio and you mentioned an Alesis drum machine. So I'm very curious as to whether that was an HR-16 or an SR-16—or maybe even an HR-B?

Well, the first drum machine I had was a Roland 606, the Drumatix. And then, in the early- to mid-Eighties, there was a lot of frustration around older equipment that wasn't MIDI. And the good thing about that, as you probably know, is as a result, you could buy old analog equipment that wasn't MIDI for next to nothing.

I mean, I think that my first TB-303, I bought for $10. My first 606 was probably $30. I have a Korg analog machine here that I think I bought for $20, as well. But my first MIDI drum machine would've been that, the Alesis HR-16.

There's a story in the book where you talk about getting that 303 from a guy for $10—from a guy who called it a “silver radio.” Do you remember where you got the 606?

Growing up in Connecticut, there were just a lot of music stores. And as a musician in the Seventies into the Eighties, my friends and I would just make these routine pilgrimages to music stores to sort of see what we could buy, what was too aspirational—to look at equipment that we would never be able to afford.

And invariably, these music stores would have lots of used, weird equipment, like old effects pedals, drum machines, etcetera. Usually at the front desk under, like, a glass case. And so I'm assuming I bought the 606 at some music store in Connecticut. I don't remember which one, because to me, they were all sort of interchangeable.

One of the advantages of the HR-16 was it was MIDI-compatible. Another was that it was also pretty cheap, relative to other stuff at the time, like the Linn and the Oberheim machines. And it also sounded good—the high sample rate. What did you like best about that machine?

My first electronic music setup—my first MIDI setup, rather, was the Alesis MMT-8 sequencer, a Yamaha TX-16 sampler, the HR-16 drum machine, and a Casio CZ101 synth. And I could do a lot with this, but it wasn't really practical.

Like, the HR-16 sounded quite good, but not for dance music. You know, the kick drums were largely unusable. The hi-hats were good. The percussion was good. Some of the snares were okay. But the kick drums really were—I mean, especially compared to some of the other drum machines you've mentioned, like the MXR or the DMX, the LinnDrum. They had usable kick drums. And as someone who wanted to make dance music, the HR-16 frustrated me to no end. Because the kick drums just were terrible.

By the time you're doing your first gig at the Palladium in New York in 1990—your accidental, first headlining gig, where you were supposed to open for Snap!, but they didn’t show—you mentioned having a drum machine in your rig at that point. So I'm assuming that by that point, you’d replaced the Alesis.

Yeah. Well, a lot of my drums were sampled. Because I realized at that time, to have great-sounding drums, I would sample breakbeats or individual drums from records that I liked. So for that particular show—at some point around ’89 or ’90, I bought a 909 at a store called Rogue Music in Manhattan. So I don't know if I had a 909 for that show, but if I didn't have one then, I got one soon after.

There's a description of that show where the discs are loading up, and you have to fill some space, and so you're playing drums off the keyboard. So I assume you had some stuff looped and you were hitting those loops?

No. That was just hitting individual keys. The keyboard I had then was a Yamaha SY-22.

Oh, man.

And so I was playing individual drum sounds on the SY-22 to try and, like, fill time while the samples loaded on the Yamaha.

I can't even imagine.

I mean, it wasn't good. (Laughs)

Your first record comes at this time where standalone drum machines were starting to be absorbed into sampling workstations. But I'm assuming the 909 shows up on that first record. Do you remember what standalone machines made it on there?

Well, the 909, as you know, became the de facto drum machine for dance music. So it's safe to say that every record I made from 1990 until about 2000 featured the 909 in some capacity. Usually the kick drum.

Like, I had a song called “Thousand” that goes up to over a thousand beats per minute, and that's just all 909. Well, 909 and a Jupiter 6.

But the 808, I couldn't afford. For some reason, I think the 909 was a lot less expensive because hip hop producers didn't want it. Every hip-hop producer in the late Eighties, early Nineties wanted an 808. So the 808s were always sort of prohibitively expensive. And I think my first 909 was probably like $500.

Not to get too esoteric here, but you mentioned an interesting thing, which I think is still true to some extent, even today. The 808 is still ubiquitous. And the 909, as you said, really has that reputation in in dance music, but it never achieved the same kind of—we’ll say, “coverage”—as the 808. Can you talk about the reasons you think that's so?

Well, I think that's because the 808—I mean, I actually would maintain that the 909 has been used on a lot more records than the 808 has, because every house record, every techno record, for a long time, they all featured the 909. The reason the 909 didn't have the same sort of iconic reputation was because the sounds were just more usable and less distinctive.

You know, like, an 808 only sounds like an 808, and it's amazing. But if you want an 808 kick drum to be super solid like a 909 kick drum, it just can't do that. Whereas 909s were a little more usable in a way, and they blended. I mean, we’re talking hundreds of thousands of tracks from so many different producers, that were all centered around the 909, but you could listen to it and not know that that's what you were hearing. I think that's why.

Animal Rights is a record where you tracked some of the stuff with a live drummer and then went back and said, “Nah, it’s gotta be a drum machine for this.” So I'm assuming the 909 ends up on that as well?

Well, until the early 2000s, the only drum machine I really used was the 909, because all of my other drum sounds were sampled. Some of them were sampled drum machine sounds. But for the most part, every record I made up until the album 18 largely was a 909 combined with drum samples. It was only in the 2000s, oddly, that I started using a lot of older drum machines.

And I think that's because—I’m stating the obvious, but with ProTools and digital audio workstations, you could suddenly bypass MIDI by just recording audio and playing around with the audio until it synced up with your MIDI. And the realization I had in 2002 was that there were hundreds, if not thousands, of drum machines that had been made, which you could never ever even begin to try and sync them up with MIDI. Because most of them didn't have even the option, you know—DIN sync or anything. But now you could play them into your ProTools and stretch them or compress them and loop them. And, that made the older drum machines a lot more usable.

That’s exactly where I was going with the next question, which is about this moment in the new millennium where drum machines have been absorbed into computer recording. Over the last 20 years or so, how often has a song actually started with a standalone drum machine, as opposed to Pro Tools, where you've got the sounds of this or that drum machine already loaded in?

Up until recently, I had the world's largest collection of drum machines. So it started because obviously, I loved drum machines in the Seventies and the Eighties, but I couldn't really afford them. And then into the Nineties, I still loved them, but I sort of forgot about them, because they weren't practical. Because you couldn't sync them up with Cubase at that time. You certainly couldn't sync them up with an ADAT or a 2-inch machine.

But in the 2000s, it was a combination of being able to use the drum machines by recording the audio and syncing it to whatever beats per minute you had. But also, eBay happened.

Yeah.

And so, I guess in 2002, I think I owned four drum machines: a 909, a 606, a 707, and probably that HR-16. But I was mainly using samples at that point. And then I started buying old drum machines, and I sort of fell in love with that process.

So to your question, a lot of times, I would get a drum machine and just turn it on and start playing along with it and record it. And if you found anything you liked, you would loop it or sync it to the track that you're working on. So, yeah, a significant percentage of the music I've made over the last 18 years has started out with some weird old drum machine.

Do you remember like the very first drum machine that you bought on eBay—the thing that really started this whole collection?

Probably it was a Rhythm King. I mean, in the early 2000s, no one else really wanted drum machines. The only person I knew who was sort of collecting them was Martin Gore from Depeche Mode. Whereas, at that point, everyone was obsessively collecting analog synths.

So I remember in the early 2000s going on eBay, and a vintage analog synths would be $4,000 and a vintage analog drum machine would be $50. So it was a wide-open field for the few of us who were obsessively buying up drum machines.

I mean, my obsession with it got so bad that I started owning multiple copies of the same drum machine. I think I had four Rhythm Kings. There was a Univox drum machine, and I realized that I had 5 of them. It got pretty obsessive.

There's a little video that I saw—that was made before you sold this stuff—about your collection. And one of the pieces that you were showing was a Wurlitzer Sideman. That that one seemed a little big and bulky to come through the eBay channels, unless you were picking it up locally. Do you remember how you came upon that one?

Yeah. It was also eBay, And basically the shipping was almost as much as buying it. (Laughs)

There were a lot of drum machines that were also amplifiers. And I had 10 of them. I mean, the very first-ever drum machine, the Chamberlain—which I had two of—it had the speaker built in. And because as you know, drum machines were designed for accompanists—whether it was people playing in churches or people playing in bars—the amplification had to be built in.

So whenever I would buy one of these big, super-heavy—I mean, those Sidemen, they probably weighed about 80 pounds—the UPS guy would just show up with this giant box. And you’d unpack it and you’d have this 80-pound wooden monstrosity.

But of all the drum machines I had, the only ones I regret selling are those ones that were also pieces of furniture. There were about 10 that were at least, like, 3 feet tall, 2 or 3 feet wide, 18 inches deep. I mean, some of them were really big. The Chamberlain was pretty gigantic.

There was an interesting line, I thought, in that video, where you were asked, about one of the drum machines, “What's it sound like?” And you said, “I haven't turned it on yet. I haven't actually done it.” Was there a waiting-for-the-right-moment kind of thing?

Well, no. The moment I got a drum machine, I turned it on. The problem was, only about 75 percent of them actually worked. (Laughs)

And so, 25 percent of my drum machine collection, maybe the light would come on. Maybe it would make some sort of sound, but it wasn't really usable. And so I would, over time, send them to some equipment repair place. But within two minutes of getting a drum machine unpacked, you would turn it on and try and figure out what it actually sounded like.

But some of the much older drum machines or the weirder, more idiosyncratic drum machines didn’t work, or they barely worked. Like, one of my favorites was, there was a synthesizer kit company called PAiA. And I had a couple PAiA drum machines, and they just barely worked. But when they did work, they were really special.

That was the orange one, the Drummer Boy. Right?

Yeah. It looked really cool and was orange, but it only made one pattern. And was a really nice pattern, when you could get it to work. Sometimes you'd need to hit it.

I read somewhere that when the time came to sell all this stuff, that it was the 909 you described as the hardest machine to let go. And I'm assuming that's the same 909 we were talking about before—that there were sentimental reasons for keeping it.

Yeah. Well, I mean, there's that one because I'd had it for such a long time, and I'd used it on so many records. But really the hardest one to let go of was the Chamberlain. Because that still stands as the most one-of-a-kind, unique, remarkable drum machine. It was the first drum machine ever made. And it ran like a Mellotron. It ran off tape loops.

When I bought it, it was the most expensive thing I think I'd ever bought. And letting that one go, that was kind of the hard one.

Can I ask, if it's not too personal a question, how much you paid for that one in particular?

Well, most of the drum machines I had, I bought for less than $100. I think that Chamberlain, because I fetishized it so much and they never came up for sale—I mean, I'd guess there are maybe 50 of them in the entire world, and even that might be generous. Like, there might only be 10. And so the first time I saw one come up for auction, it was in great shape. I think it was $4,000.

Was that the one you were able to get?

I actually ended up buying two of them. The first one was in pristine condition, and I bought it for $4,000. And the second one was for parts, and I think that was, like, $1,000.

You built this collection up, and you once even described it as the Noah's Ark for drum machines. So what was the epiphany where you realized, I gotta get rid of this stuff?

Well, I guess it was about five years ago. I had two very big storage lockers filled with equipment and I had—I mean, just so much stuff that I'd accumulated over the years of touring, of buying equipment. And the truth is, I used approximately 1 percent of it.

Like, I had a Jupiter 6, two Juno 106es, a bunch of MOOGs, a beautiful—I think it was either a Rhodes or a Wurlitzer electric piano. Just so much stuff, and it never got used. And it felt like such a shame. Why did I have all this wonderful stuff sitting in storage, collecting dust? Same thing with my records. I had thousands of records that simply never got played.

And I just thought, you know what? If I sell my drum machines, if I sell my equipment, if I sell my records, I can generate money for charity, and the people I sell them to will actually use them, or will actually listen to the vinyl.

It will mean way more to someone who's buying one special drum machine, for them to own it than for me to have three or four hundred of them sitting in a storage locker, collecting dust.

Did you ever consider turning this collection into some sort of museum?

Yeah, definitely. I used to sort of absurdly think of starting the world's only drum machine museum. But then I realized there were just other things I'd rather do.

However, when it comes to drum machines, I did keep, I think, five drum machines. And the ones I kept, I kept four Electro-Harmonix drum machines. The DRM32 is one.

I forget what they’re all called, but I basically kept one of each. I actually just posted about it on social media last week. I forget what it's called, but it's in my studio. It does something that no other drum machine I've ever encountered does: it has an external in, an audio in, that takes an audio signal and passes it through the drum program. And so you get a gated sequence of the audio based on the drum program. It’s the only one of the 400 drum machines I had—this is the only one that did that. And so I did keep that one.

This might have been in the same video I mentioned earlier, but I remember that you were showing the Electro-Harmonix drum machines. And you said, look, if my apartment was on fire, these Electro-Harmonix machines are what I would grab. Why those in particular?

Part of it is that I believe, as far as I know, Electro-Harmonix was a New York based company. I think they're based out of Long Island. And these drum machines, they have a swing to them. A lot of other drum machines like the 909, the 808, when you started being able to program, you could program in swing—shuffle or swing, whatever they would call it.

But most drum machines were—as much as I loved them, they were quite rigid. You know, when you listen to older analog drum machines, the programming—it’s quantized to within an inch of its life. It's very straight.

And these Electro-Harmonix drum machines, whoever programmed them just programmed in swing. And you can tell, clearly, they were built during the disco era, because they have this disco swing to them. And that's that's why I kept them.

Well, I was certainly hoping that talking about all of this stuff you got rid of wasn't going to stir anything up for you.

Oh, no. Not at all. Because like I said, 99 percent of the time, I wasn't using them.

The vinyl was a little more emotionally challenging, you know—getting rid of my mom's records, getting rid of the records that I was obsessed with in elementary school. That's more challenging. But there's something nice about just getting rid of stuff you don't actually use.

If anybody can answer this question, it would probably be you. What's the most overrated drum machine ever?

Honestly, that Rhythm King is really not…I guess what made it special is you could play individual sounds on it. But the programs on the Rhythm King, the original one, really are just not that great.

I would say the LinnDrum and maybe the DMX to an extent, I just found them to be a little bit like—they’re only really good for one thing. But then, to be fair, the LinnDrum I had barely worked, so I'm not the best judge of it.

I mean, I appreciate your question. To be honest with you, I don't think there is such a thing as a bad drum machine made before 1984. Even the early digital-analog hybrids like the 909. After 1984, when they became exclusively digital, I think that's when you can dismiss them. Maybe I'm just too much in love with drum machines, but every drum machine made before 1984 is special.

This question can mean different things in different styles of music, but who's the best drum machine programmer you've ever heard?

Boy, that's a hard one to answer. The name that first brings to mind— and it might not be fair, because I don't know if he actually did his drum machine programming, or if someone else worked on it—but Arthur Baker comes to mind. I mean, I listened to New Order’s “Confusion”—the sequences and the drum machine programming on that.

Todd Terry—but then again, I think Todd Terry just used drum machine samples. He had that Akai sampler, the 1200, that everybody used. [So] as far as a drum machine—it’s the obvious answer, but it's the right answer—would either be Arthur Baker or Kraftwerk.

So you've divested yourself of your drum machine collection—

Oh, sorry to interrupt. I just remembered the actual first drum machine I ever had, way, way, way back, was the Mattel Synsonics.

Oh, I had those too! That is awesome.

I don't know why I forgot about it but a few years before I got my 606, it was my my Christmas present. I think in 1983 or 1984, my Christmas present from my mom was the Mattel Synsonics drum machine.

If it was 1984, we got them for Christmas the same year! Did you have one of those in your collection, too?

Yeah. I think I had three. Because there was the original one I had, but then also they had that slightly fancier one that had, I think, almost like an addition, like an attachment, if you remember. And then they had one that I don't know if it was a speaker or what, but it had something attached to the top of it.

(Editor’s note: There was indeed a Synsonics model that included a footswitch, which allowed a user to control “accent” and “tempo.”)

And you could, in its limited way, you could program that stuff. Right? And most of the sounds, if I remember correctly, were tunable.

(Editor’s note: The Synsonics had a tunable tom-tom. The “Pro” model also allowed users to save patterns even after the machine was powered off, which was an unusual feature for such a budget-priced machine, along with the velocity-sensitive pads. The members of Kraftwerk, by the way, were reportedly big fans of this machine.)

It was really surprisingly special. You know, I have cassettes of songs—because in 1984, ’85, that was all I had for electronic drums. So yeah, I need to go back and dig out my old cassettes of demos I made back then.

I’m glad you remembered the Synsonics! I was going to ask, though: you amassed this drum machine collection and then you divested yourself of it. But can you see yourself ever buying another drum machine?

Well, there's one for me, there's one holy grail of drum machines. It was an Italian drum machine. I think it's called the EKO.

And I bought one, but it didn't work and I couldn't get it fixed. But I think that's the one I'm thinking of. And I remember looking at a YouTube video…and the sequence, or the drum machine pattern I heard from this was so special. So if anything could tempt me to buy another drum machine, it would be finding that.

I wondered if there’s anybody that you would recommend talking to for this book?

Well, obviously, Richie Hawtin comes to mind. Richie [AKA Plastikman], I think his dad was a technician at General Motors. And so in 1992, I toured with Richie and the Prodigy, and Richie had a 909 and I think a 707, maybe some other things that his dad had modified.

And they were such remarkable instruments, covered in switches and dials that did everything to the sounds of a 909 and the other drum machines that you could possibly imagine. So he used his drum machines in ways that I don't think too many people ever did.

I remember because he was touring with his friend, Dan Bell. They're both producers from, Detroit and, London, Ontario. And I remember the first day they showed up with these completely modified drum machines and 303s and everything.

And I was so intimidated because I just had no idea. I didn't even know you could do that. That you could cut open a drum machine and modify everything—modify the pitch, modify the attack. I didn't know you could actually do that.

This has really been great. Anything we didn’t cover that we should have?

There's one other thing I just wanted to bring up. One of the reasons I collected drum machines is because it's very easy to focus on the cool side of drum machines, whether it's Kraftwerk or New Order or early hip hop or house music or techno. But I also really loved the Sixties, early Seventies, completely uncool aspect of drum machines. You know, the guy playing organ in a church basement, the guy with—what was that? A Seeberg Select-A-Rhythm?

Yeah.

I loved when I would buy these drum machines, especially the older ones. One of the best things about them was—I mean, they sounded nice, but they came with literal inscribed history. Like, you would look at the drum machine and they'd be covered in pen and pencil marks, from whoever had been using it in a church basement or a Holiday Inn lounge somewhere.

And that, in a weird way, that was one of the most precious aspects, was thinking of the history. Thinking of some guy in Sacramento, playing at church on Sunday and playing at the local Marriott Inn on Tuesday nights with his drum machine, and drawing in pencil, like, what the settings were supposed to be when he played old cover songs.

You actually had a great quote about that in in one of these videos I saw. You said, “Look, you don't sweat on a plug-in.” And I guess that's speaking to the same thing. These machines have some life all over them.

Yeah. A lot of people did really cool, groundbreaking things with them. But a lot of people just played Neil Diamond covers in Holiday Inn Lounges in New Jersey. And to me, that's just as special and important in the history of drum machines.

A whole lot of my drum machines—and they were really unusable—were the ones that were built to be mounted under a church organ. Yeah. There were a couple that are four feet long or three feet wide and about three inches tall. They were built specifically to be screwed to the bottom of a church organ. And I love them, but there's nothing less cool than a drum machine only designed to be used by old ladies at church.

But I just love the fact that there's this historical link between the old lady at church and, you know, Arthur Baker. Because while the old lady at church was playing hymns with her drum machine, Sly and the Family Stone were using the exact same drum machine, probably on the other side of town. There's not too many instruments that you can say that about. And I love that dichotomy, if that's the right word for it, as well.

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple Books, and other online retailers.