One of the many paradoxes of drum machines is this: when they began appearing during the Seventies and Eighties, the standard criticism was that they were too perfect, and were draining the human element from music.

Yet when you talk to the pioneers of drum machines today, many will tell you that it was the imperfections of those early machines that they most prized.

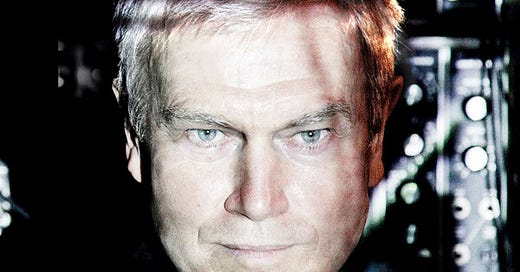

Some of those users, in fact, still treasure the quirks of the old analog rhythm boxes. John Foxx, the former lead singer of Ultravox, and one of the giants of electronic music, certainly falls into that category.

“Those early drum machines are intrinsically risky units. They move in and out of time slightly in a strangely organic way, and that’s another factor that gives a certain endearing warmth,” says Foxx. And those machines, he adds, helped give the music of the late Seventies and early Eighties—including works like his own solo albums Metamatic and The Garden—their character, which he remembers as “ragged, alive, beautifully imperfect—and fun.”

At age 74, Foxx continues to innovate artistically. And he continues to use the vintage drum machines that he helped bring into the mainstream. Some of them show up in his current electro-rock outfit, John Foxx and the Maths, which includes Foxx’s fellow drum machine enthusiast Benge.

In Part II of my conversation with Foxx for the book Dancing to the Drum Machine: How Electronic Percussion Conquered the World, we talk about his all-time favorite drum machines, how he lost his way in the “showbizzy” Eighties and found his way back, and how to “rescue an entire generation from the skip.”

In the Metamatic-era appearances you made on Top of the Pops, you often appeared with a group of synthesists. But I recently saw the clip of “Europe After the Rain” and noticed that the drum kit was present, yet left vacant. Was that any sort of statement about drummers and drum machines—or did the drummer just not show up?

It was simply that the Beeb assumed every band had a drummer, so they automatically put a kit onstage. I thought it a good idea to leave it unused.

On your second solo album, The Garden, you began using the Linn LM-1—I believe you said at one point that it was the first Linn machine in England? That machine was a game-changer because of its sampled sounds.

I have always assumed that the Linn was chosen in part because it fitted the more pastoral and “acoustic” feel of the record, the reaction you have described against the hard, spare sound of Metamatic. Is that accurate?

I seem to remember using a Movement Drum Computer on some tracks, but when the Linn arrived, that was the end of it. The company that brought it to the studio told me it was the first in England, and it was still a prototype. They warned me it wouldn’t easily resynchronize with the code you’d lay down, and we discovered that was the case.

But it was so easy to use. I used that Linn on many of the tracks, some in combination with a talented drummer, Phil Edwards. But Phil had to leave the sessions before we’d finished, so Duncan Bridgeman, a great and dexterous musician, would add appropriate fills manually, using the buttons live, so we didn’t have to resynchronize it.

I also remember using it for “The Garden” track itself and how we had to detune and re-equalize it completely to get those deep sounds, but we managed.

Benge has a Linn now, and I really enjoyed using it again recently. A great, powerful, but tight sound.

I think there’s also a Roland 808 listed in the credits of The Garden, as well as a machine that people seem to have had a love/hate relationship with, which you just mentioned: the infamous Movement Drum Computer. (I interviewed Mike Howlett recently, and he had quite a bit to say about this device!) Could you talk about the use of those two machines: why you chose them and how you used them on this record?

I loved the 808. I still think it’s the best-ever drum machine—the right balance of controllability and fabulous sounds. Perhaps it’s a bit over-used now, but that and the 909 bass drum made unbeatably powerful percussion tracks. I remember using it particularly on “This Jungle” and a few other songs.

I don’t remember much about the Movement Drum Computer. I’d often get new equipment in on sessions on approval, use it once, then send it back if it wasn’t satisfactory. The LinnDrum really wiped that one out.

The Golden Section is an album that you once described as “my own version of pop music. I kind of imagined a jukebox in a place I'd never been to before—a country that was a sort of annex from the rest of the world…Something that might have existed if, say, I'd never done Metamatic and The Beatles had never gone out of fashion.”

On this album, you used some live drums, played by Blair Cunningham I believe, but also some programming. How did you view the role of drums and drum machines in creating this new aesthetic?

Well, in my wee head I was kicking off from when the Beatles and George Martin had made “Tomorrow Never Knows” from a drum loop and no other conventional noises.

That was really the blueprint for a lot of things I wanted to do. The first properly modern song that you couldn’t have made outside a recording studio. It used the studio as another instrument and so prefigured the entire future of recording. The moment the medium became the message, as [Marshall] McLuhan might have said.

I wanted to revisit and update the Beatles more avant-psychedelia, using drum machines and synths, as well as guitars. The Pistols had declared all that ungood, but I felt it was a neglected and valuable avenue worthy of revisiting—seminal, in fact. This was about ten years before Manchester recovered all that in a very similar way.

By the mid-Eighties, you have said you had lost your way, musically. Was any of this related to the fact that the industry had caught up—at least in a technical sense—with some of the innovations you had helped pioneer?

Perhaps some of that—but sampling had something to do with making everything so perfected it all seemed a bit mild and clean. The term “perfect pop” got bandied about.

I hated that. Always instinctively detested perfection attempts. It became so claustrophobic. Everything became so dull and smug and orthodox, instead of being ragged, alive, beautifully imperfect—and fun.

In a related question, it seems in retrospect that you chose the exact right moment to withdraw from pop music. The second half of the ‘80s was dominated by Stock-Aitken-Waterman productions, and the new, all-digital sound. Did you listen to much pop music during this time? If you did, what was your reaction to it?

I’m really only comfortable when things are distorted and slightly out of tune and a bit louche. I simply felt it had all become very conventional and a kind of showbizzy dullness was dominant, but selling like hot cakes, so the record labels loved it.

I couldn’t see where I might fit into this shiny world, and I’d begun to realize I despised myself for my own semi-conscious attempts to negotiate it. Really I should have picked up an electric guitar and written some more nasty songs, but no one was interested. I think there was only The Cure and one or two others that I actually liked at that point.

When you returned around the turn of the decade with Tim Simenon in what would become Nation 12, you’ve described how much fun the project was—especially using “vintage” electronic gear that you sometimes had to track down at pawn shops because it was out of fashion. Reading this made me wonder: if we think of the vogue for sampling that occurred at this time as a reaction to the sterile, digital sounds that predominated in the late ‘80s (by allowing producers to access warmer, analog-recorded loops from old records), then perhaps this project came from a similar impulse? Using vintage analog gear instead of the digital workstations that were beginning to proliferate?

(I’m thinking as well here of a quote from an interview you did a few years ago, in which you stated, “To use analogue now is to recover something which everyone recognizes but which has been lost amid the rush of popular technology. In a coarser way, it’s a bit like rediscovering black-and-white photography after color photography came out. Because everyone jettisoned it, thinking that’s old-fashioned now, but then ten years later everyone started looking at old black and white photography and thinking, ‘Gosh, that’s really special, isn’t it? It’s totally different, you can’t do it like this anymore. Where can we buy the old film-stock?’ And that stock tells a story, tells a different story, to the new stuff.”)

Absolutely—there was such a rush of digital innovation after 1982 that analogue equipment was abandoned before it had been properly explored. That’s what Benge is all about. He wants to complete the exploration. He rescued an entire generation from the skip.

You’ve gone back to the CR-78 on some recent recordings, including Evidence of Time Travel, where you have described it as the lead instrument.

That’s how I think of it in that album. It gives the entire record its identity.

I’ve seen some live equipment lists where you have it in your arsenal; do you actually use the machine(s) proper on your recent recordings, both solo and with The Maths (as opposed to samples)? If you do, is it because of the sounds themselves? Is it the tactile sense that drum machines provide, that samplers and Pro Tools et al do not?

We certainly don’t use samples. I still like buttons and knobs—hate and detest multifunction menus. I want it all laid out and alterable simultaneously on a single panel before me. Fiddling about between menus will kill any excitement and any good ideas. It’s simply bad design and I won’t ever touch it.

Those early drum machines are intrinsically risky units. They move in and out of time slightly in a strangely organic way, and that’s another factor that gives a certain endearing warmth. If you try to clean it all up too much, it often loses that feel you started off being inspired by, and the recording sort of crumbles in your hands.

Just as producers have come to enjoy incidental sounds, crackle, tape hiss and record surface noise, etc., it works best if you simply enjoy the grit and wonk and work along with it.

There are some other vintage machines that have been listed as part of your live setup, like the Amdek Percussion Synthesizer and the Klone Drum.

These are brought in and used by Benge—I really like them, of course, and often use them during recording, but Benge is also a real drummer, so I tend to leave fills and many basic rhythm structure to him, though I will always use a loop I devise for the basis of each demo. This gets transposed into Benge’s machinery later, with adaptations and more detail. Often, it gets completely replaced.

Basically, everything available got investigated during that early period, but few survived. They’d often be used once, then discarded. The survivors got adopted—the [Roland] TR-77, the 808, the CR-78, the Linn, the Simmons kits. (I got John Walker, the engineer for Vangelis, to build me a set of Simmons units with triggers operated by a keyboard or a sound from tape. Very useful.) We still use some of these units now.

Can you speak about the role of drum machines—which I assume were played/programmed by Benge—on the new Maths single, “Howl,” and on the forthcoming album?

I think it’s better if he speaks about that, since he’s the one who would operate most of it in the final versions. But I will say one of our precepts for “Howl” was the looseness and power of guitars allied with hand-played and sequenced synths and the force of machine drums. All that together allows an organic/electric tension that we’ve both grown to love.

I also must add the vast importance of reggae and dub to this—a system where each isolated sound was valued in itself and often allowed complete momentary dominance, to everyone’s great delight—especially on the dance floor.

This presaged the isolation of sounds that producers and artists were aiming at—and the entire future of R&B, grime, hip hop, etc. I always use dub in mixing and have done since Metamatic. You can make radical scene changes, cuts and exposures that add fantastically to the tracks. They become the song, eventually.

Working with Robin Simon again will put lots of folks in mind of Ultravox, but he also played on the three albums that followed Metamatic. “Howl” is pretty aggressive, compared to those releases, but does the new Maths album pick up any of the threads of those three solo records, thanks to his presence?

Yes, I think so. Robin represents the link of purity between a set of pure intentions, over a muddled and wasted middle period, to now.

I assume you have done a lot of the programming of drum machines over the years on your projects. I wondered, though—because programming drum machines is a particular skill that people rarely have been lauded for, unless perhaps we’re talking about Prince—who the best drum programmer you have ever worked with has been?

Well, there are two I can think that I haven’t worked with—Guy Fixsen, who did Lone Lady’s first album—and either producer Robin Millar or Martin Ditcham, who did Sade’s first couple of records, though those were a mix of live drums and triggered parts, I believe. But ironically, the end result sounds like good, fluid, drum machine programming. Paul Cook and Dave Early were the drummers. It’s all an interesting example of drum machine sounds influencing the sound of real drums—another step in the sonic processing game.

By the way, I’m sure Sade must have heard the first electronic samba record ever made, “The Boy From Ipanema,” which Gareth [Jones] and I produced in 1982 for a Belgian band, Antena. Sade’s first record came out a couple of years later.

At present there are some great American hip hop and R&B programmers, though I tend not to enjoy much else other than the drums and the odd spare synth part on these records. I also like Luis Valdez of The Soft Moon. He has a nice outrageous ferocity.

You clearly have a special relationship with the CR-78. If you could only pick one drum machine to use for the remainder of your music-making career, though, which one would you pick, and why?

I’d use an 808 because it can be varied so much and I love the sounds it makes—they’re absolute killers and nothing at all like real drums.

But in the end, it would be impossible to give up the CR-78. It’s become my sonic signature—and every time I turn it on, it turns me on. That’s what you really want from a piece of equipment.

Tune in for more full interviews with the pioneers of drum machines, coming soon!

Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.