Spoilers: this is not a piece about drum machines, nor about technology. It is about appreciating music, and musicians, though—and since that’s what first sparked my love of drum machines, I hope you’ll find it appropriate for this forum nonetheless.

He was standing in front of the club, smoking a cigarette.

I was inside, just a hundred feet or so away—Pittsburgh’s Club Cafe is a teeny-tiny venue—watching him through the front windows.

He pulled out his phone and took a couple of pictures. No one else was on the street on this chilly spring evening. No one else walked by. No one else left the club to go outside. I waited. And waited some more.

In twenty seconds, I could have stepped through the door, gone outside and introduced myself. Could have shaken hands; could have taken a selfie, even though that’s not normally my thing.

But far more important is what I knew I ought to do. That is, tell Tommy Keene how much his music had meant to me over the past 30 years.

I’d praised his music in print. And I’d interviewed him a few times, where I’m sure I’d let my fandom slip. This was different, though. The right thing to do was to go outside and say what needed to be said in person, during this break before he came inside and got ready for his headlining set.

I didn’t, though. I just stood there, and the moment passed. He looked up at the marquee, hands in the pockets of his jeans, then peered up and down the street. The club was mostly full, although that equated to probably a hundred or so patrons. A few more would have fit, and I wondered if he were waiting to see if anyone else showed up.

They should have, just like more people should have paid attention to the records he made. But they didn’t. So he came inside, picked up his 12-string guitar, and got on with things, as he always did.

What I should have done that night, and didn’t, has stuck with me ever since.

I can’t remember now exactly what my rationalization was. Probably it was the one that I’ve heard other veteran journalists use: “He’s heard all this hundreds of times before.”

Why go out there and force the guy to hear yet another middle-aged confession? It’s probably depressing for him. He’ll have to smile and fake interest. Don’t make him do that before he has to play a set in front of a bunch of other middle-aged fans just like you.

And on and on and on.

But I knew, even as I rationalized it, that this was a mistake. That even if they have heard it hundreds, or thousands, or even millions of times before, you owe people something, if they create art that moves you. To hear that tribute, however trite and lame, is better than not hearing it at all.

Because not hearing it at all is what they get from the vast majority of the world. Even, sometimes, the vast majority of the music-loving world.

So I shirked my duty that April evening. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the show—the first time I’d ever heard Tommy Keene live—every bit as much as I thought I would. And I figured the next time our paths crossed, I’d make up for this failure—maybe even in the form of a funny little story.

Until six months later, when I woke up one day during Thanksgiving weekend and found out there wouldn’t be a next time. Tommy Keene had died in his sleep in Los Angeles, at age 59.

***

The first time I interviewed Tommy Keene, right around the turn of the century, I asked him about an interview he’d done where he said he’d probably quit music in five years if he weren’t further along in his career.

He thought about this for a moment and then asked, “Is the five years up yet?”

That answer, I would learn, was characteristic. Keene was a master at using humor—especially of the self-deprecating style—to deflect any disappointment he might have felt about not being better known.

And he should certainly have been better known. After emerging from the D.C. new wave scene (where he was in a band called The Rage with another should’ve-been-bigger singer-songwriter, Richard X. Heyman) in the early Eighties, Keene spent the next three decades showing off his writing skills and guitar chops on a series of expertly crafted power-pop records. None were bad; a few were classics.

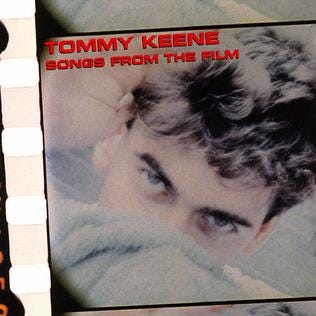

The first of the latter was his 1986 major label debut, Songs From the Film. I bought it the spring of my senior year in high school, after reading a blurb in Musician magazine. Underneath the big drums and studio sheen applied by former Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, there was a wistfulness that spoke to me, and still does, nearly forty years later. It’s best encapsulated in “Places That Are Gone,” which was probably Keene’s anthem.

But it’s a thread that runs all through his catalog, and it surfaces most clearly in what I think are his best songs, from fan favorites like “Astronomy” and “Nothing Can Change You” to lesser-known gems such as “No One in This City.”

Some would argue, and have, that this melancholic streak was a result of being gay; Keene finally came out in 2006. Perhaps, but I think that’s far too limiting an interpretation. Tommy Keene’s songs acknowledge the restlessness in all of us, the sense that things, even at their best, are never quite right. That is simply the human condition: we are all out of place. And I think Tommy Keene spoke to that, and to all of us. It’s just that not enough people seemed to be listening.

After his death, Esquire would publish a smart and sensitive obituary titled “Tommy Keene Should Have Been Bigger. But He Didn't Need to Be.” The author, Dave Holmes, pointed out that “If you knew about Tommy Keene, one of the things you knew was that more people should have known about Tommy Keene.”

For a while, way back when, it looked like that might actually happen. That summer of 1986, I went with my then-girlfriend to see one of the truly awful movies of its era: Out of Bounds, which tried unsuccessfully to recast nerdy Brat Packer Anthony Michael Hall as an action hero.

But the soundtrack contained a handful of what we’d later call “alternative” artists, and Tommy Keene was one of them. I’m pretty sure I was the only person in the theater cheering when he made his two-minute cameo playing “Run Now” in the Stardust club. (He even had to duck when Anthony Michael Hall, sporting his fingerless black gloves and new wave girlfriend Dizz, was being chased across the stage by some small-time thug.) “Run Now” was produced by Bob Clearmountain, with those huge Bryan Adams drums from songs like the similarly named “Run to You,” and it was, to that point, Keene’s most unequivocal commercial effort. But it didn’t land.

(I have a recording somewhere of an interview where Keene told a truly funny story about being at a disastrous party around this time with his Geffen labelmates Siouxsie and the Banshees, who also appeared on the Out of Bounds soundtrack and in the film. I can’t recall the specifics, but what I do remember is Keene expressing that same sense of not belonging. He was slightly bemused, yet there was an air of melancholy about the tale, a sense of “How could I have imagined that things were going to turn out differently?)

What’s really a shame is that four of the six songs on the Run Now EP were expertly produced by Don Dixon, the genius who oversaw so many power-pop classics during the Eighties. The best of the quartet, “Back Again (Try),” is yet another wistful gem that Keene played at Club Cafe.

Keene made another album for Geffen, 1989’s somber Based on Happy Times. It was a fraught undertaking; the label was desperate for a hit, and tried pairing Keene with a series of co-writers, from Bryan Adams’ lyricist to The Replacements’ Paul Westerburg.

In the end, it was a pair of co-writes with kindred spirit Jules Shear (who’d had a series of hit covers by other artists, like Cyndi Lauper’s “All Through the Night” and The Bangles’ “If She Knew What She Wants”) that proved most successful. I was ecstatic when Keene played one of them at Club Cafe: the disc-opener “Nothing Can Change You.”

But it’s a dark-hued collection overall, culminating with the suicidal overtones of “A Way Out.”

Keene was dropped by Geffen, of course. After a couple of releases on then-California based indie label Alias, he truly resurfaced in 1996 with Ten Years After. A decade beyond Songs from the Film, Keene came up with an album just about as strong and inviting. Produced by Adam Schmitt, yet another member of the should’ve-been-bigger power-pop club, and recorded as a trio, it was just about everything you could have hoped for from a Tommy Keene album.

Yet the celebration, as ever, was muted. “Don’t look back/You will never ask for more,” he sang in “Silent Town.” Was that advice for us, or for the writer? Or for both?

***

The second time I interviewed Tommy Keene, I fell hook, line, and sinker for a silly ruse.

“I read the press release, and it said ‘Warren in the Sixties’ is actually about the Warren Commission?” I began, hesitantly. “That doesn’t seem right.”

“No, no, no,” he replied, sounding embarrassed. “I have this publicist who thinks that kind of thing is funny.” He sighed, suggesting that he felt otherwise. “It’s about Warren Beatty.”

The song was on the 2006 album Crashing the Ether. By this point, Keene had settled into a steady schedule of production: every two or three years, he’d put out a new record, do a tour, and receive the usual accolades. “Criminally ignored” is a term I used more than once to describe him, but it was hardly an original thought.

There was a moment, though, the next time we spoke, when Keene’s witty reserve dropped momentarily.

I had just listened to his new album, 2009’s In the Late Bright, and my friend Annie Zaleski had commissioned me to write about it for The Riverfront Times. I wanted to ask about a new song—a song that seemed to me to be an even more surefire hit than “Run Now.” It was just two chords, but it had a basic beauty that I thought just about anyone could grasp on first listen. (Years of writing about music had finally taught me that the more complicated songs I often loved were probably not hit-bound, in part because of their complexity.)

"I know which song you're gonna say," Keene said, before I could even mention the title. And he was right, of course: “Save This Harmony” sounds now, as it sounded then, like it has the instant familiarity of a classic.

"I was incredibly excited all the way through the recording process," he told me. "I had the feeling that, of any song I'd done in quite awhile, it was the most commercial, the most universal. It's such a simple, basic song, that if someone else did it, it could be a hit. To me, it sounds like a U2 ballad off one of their later records.”

As I wrote then:

What's most revealing about "Save This Harmony," however, is the way that talking about it exposes the hopeful side of Keene, something his sharp sense of humor — honed by a string of record industry near-misses and misadventures — usually deflects.

"It's frustrating, because that's the song I'm kind of really counting on...my ace in the hole, to get picked up by a movie, or TV, or someone else covering it," he admits. "That's the only avenue that could be open to me, to turn this whole thing into something bigger and more productive."

In the end, that happy eventuality did not come to pass. And so it was that nearly a decade later, I waited too long to walk outside at the Club Cafe and say my thanks—another happy eventuality that never came to be.

***

I actually found the photo that Tommy Keene took that night in Pittsburgh, on his Instagram. It’s one of a series of on-tour shots, venues and posters and soundchecks and even a few in-the-car pictures of what I assume are his shoes, with a handsome set of checkerboard laces.

It would be wonderful to wring some surprising insight out of this non-encounter. I think that’s neither likely, nor appropriate.

Just as cliches are simply truths that are too true to maintain their power, what I learned from my failure to act here is no more revelatory than the same advice you’ve heard from family members and friends and even perfect strangers a million times: that it’s important to say the important things while they can still be said.

To say it years later in written form is some way of addressing the issue, but incompletely and, inevitably, unsatisfactorily.

Had I walked out into that brisk April evening and said my thanks in person—my thanks for the hours and hours of pleasure that Tommy Keene’s recordings had brought me over the years, perhaps even the way they shaped my adolescence at a most formative time, or the way they communicated something that I think he wanted to communicate—well, it might have been embarrassing. Cringe.

But it might not have been. In fact, I suspect that it wouldn’t have been at all.

If you find yourself in the same situation, don’t make the same mistake. We give in to cynicism in innumerable ways every day. This should not be one of those ways. If you have a chance to say what something or someone really means to you, then there’s no value holding that back.

When those places that are gone are gone, perhaps they always stay with us. But if you can make them better, with a word, while they’re here in the here and now, then do.

Visit Tommy’s webpage, and also his Bandcamp store—there’s a brand-new release out with an outtake from Songs From the Film!

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple Books, and other online retailers.