Last Beer; Best Beats

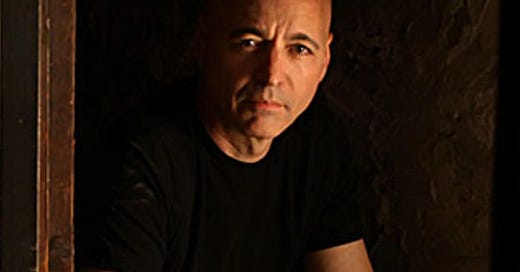

An in-depth interview with session drummer extraordinaire Sammy Merendino, Part I

After their father’s death, Sammy Merendino’s brother shared some paperwork with him. It’s the kind of thing that happens often after the passing of a parent.

But in this case, the documents revealed something surprising and crucial—something that helped send Merendino on his way to a career as one of the top studio drummers of all time.

The papers showed that in the early Eighties, Merendino’s father had put the family home up for collateral. He’d placed a lien on the house to pay for a LinnDrum—which Merendino, trying to get a foothold in the rough-and-tumble world of New York City session work, had realized that he needed.

“And he never told me that,” marvels Merendino. “And I ended up paying it off in about six months. He was such an awesome guy.”

Merendino got the LinnDrum—and much more. He became Larry Blackmon’s drummer of choice in Cameo, playing on one of the decade’s best-selling and most influential albums, Word Up. And he went on to play with a Who’s Who of music’s biggest names, from Michael Jackson and Aretha Franklin to The Beach Boys and Hall and Oates, from Carly Simon to Billy Joel to Lou Reed. You’ve probably heard him on Hank Williams Jr.’s Monday Night Football theme, or the opening music from Nightline or World News Tonight, or the more than 1,000 commercials for which he provided drums—and drum programming.

There are actually two turning points in Merendino’s drum machine odyssey. His father’s cosigning for a LinnDrum loan was one; the other may be even more remarkable. He talks about it in Part I of this exclusive two-part interview.

I ask just about everyone this question: Do you remember the first time you ever heard a drum machine—on a record; in a shop; in someone’s home organ?

Well, everybody's heard Rhythm Aces, but I remember being a kid and hearing those. Especially Sly used to use those to record with, and I’d heard them on the Sly records. But even before that I heard—I used to work in a music store and sell pianos and organs, and all the organs had those.

But the one that really—the first time I heard one that made me say, "Oh yeah, that's the thing”—it's an English band, and they covered that tune "Always Something There to Remind Me.”

Naked Eyes!

Yeah, Naked Eyes. I heard that track and I was just knocked off my feet. "Doom da doom,” the tom fills, and the whole thing. I just remember hearing that track and going, “Oh, this is gonna be something.”

Do you remember a point, as a drummer, where you were thinking, “I gotta figure drum machines out?

Well, I actually bought a drum machine. And the reason I bought it was just to work on my time. I was on the road for a year and a half, and when I got off the road, I was based in New York. And I was like, “Man, I really gotta make sure I'm as good as everybody else."

So the first drum machine I bought was a Roland...I think it was a Roland 606? (Editor’s note: The TR-606—also called the Drumatix—was released in 1981. It’s the same machine Steve Albini would make famous in the postpunk band Big Black.) Just a little tiny machine. And I had that for about a week, and I was like I need a LinnDrum; I’ve got to get a LinnDrum.

And so, I called my father and asked if he would cosign a loan. Because back then, the LinnDrum—this was back in 1982—was $3,000. Which is a lot of dough when you're not working. So I asked my father to cosign a loan for me to get it and he was like yeah, no problem.

And it turns out later—and this is just a sort of an aside—I found out he had put a lien on his house to get that loan for me. And he never told me that. And I ended up paying it off in about six months. After he died, my brother sent me the agreement, and it showed that he had put the house up as collateral for me to get that drum machine. He was such an awesome guy.

I bought that machine to start practicing with, to get my time together and to just really lock in with. I got tired of practicing with a click [track], and I wanted another percussionist. But it ended up, it just took on a whole life of its own. I got really into it and just started—I liked the sound of it. It was a different sound, a different feel; it made me analyze everything deeper, and it was just really exciting. I had been playing drums since was 12; drums are like God almighty. But at that point, I’m like, "This is good. This is a cool thing.” And I met some guys...you want all this information?

Absolutely!

So I had the drum machine and I was using it, seeing there was something happening with it. And I was getting sounds for it and stuff. Anyway, I was on my way to audition for the Psychedelic Furs and I was down to my last five bucks.

I had just moved from Queens—I had this place in Queens, and I had moved into SoHo, so I'm on my way to this audition. And I’m early. So I stopped in this bar, the Prince Street bar, and it was like 4 o’clock in the afternoon, I was like, “I might as well get a beer.” I remember this vividly: it was $2.75 for the beer, and I was like, “I can't even afford two beers.” So I gave the bartender the five bucks, and I was like, "Just keep it. I can't do anything with it.”

So I’m sitting there drinking this beer, waiting to go to this audition, and these two guys are talking at the other end of the bar. And they're saying, "So what do you want to do in the session tomorrow? Do you want to hire a drummer, or get someone who's got a drum machine?" And I said, "I've got a drum machine!” And they're like, "Really? Are you any good?" And I said, "I’m the best in New York City. There’s nobody better than me.”

They said, “Well, great. The session’s tomorrow. What do you charge?" I said, "What do you pay?” And they said, “Well, 50 bucks.” And so in my head, I'm thinking, 50 bucks, I really need 50 bucks. And I said, “Well, it’s a little bit skinny, but I’ll do it. I’ll do it for you."

So I get their number—back then there’s no cells, so we just trade phone numbers—and I go to the Furs’ audition. It turns out I had another second-place finish: I had a string of second place finishes—always the bridesmaid, never the bride. I was the next guy, always!

(Editor’s note: Placing this audition is tricky. The best guess is that this anecdote might have occurred sometime in 1983. The audition would presumably have been for the Furs’ Mirror Moves tour, which would mean that Merendino was bested by the session man Paul Garisto, who would go on to play with the Furs for the next five years. And the Our Daughter’s Wedding single in question would then have been the song “Take Me,” released in 1984 and produced by Steve Rosen, whom Merendino mentions. If you give the song a listen, those drum sounds might well have been a Linn, augmented with some other electronic percussion.)

So I go to do this session, and the name of the band was Our Daughter’s Wedding. Do you remember them?

Oh yeah! “Lawnchairs”!

Well, I go to do this session, and it's at this studio, Park South Studios on West 58th Street. And it turns out amazing—it’s just really great, and so I met this guy, Steve Rosen. He was the studio manager, and we're still friends to this day. Steve was instrumental in my career. He told the owner of the studio—who was this guy Joe Venneri, who was in the band The Tokens, and was also producing records—Steve told him, "You gotta start using this guy on everything.”

So I started doing all these sessions at Park South anything that came in there I would do. You know, like [drum programmer] Jimmy [Bralower] had his Power Station thing. I was like that at Park South I was in all of those sessions. So I’d do all these demos for people and all this different stuff.

They brought in the Weather Girls’ second record, so I’m in there doing that record. And I laid down a track, and they’re doing some overdubs on it and I'm sitting out in the lobby just reading the newspaper. And some guys walk in, and I hear this big deep voice go, “Hey, who’s the drummer on that? Who did that? It sounds great!” And I look up and say, “Ah, that was me.” And it was Larry Blackmon from Cameo. He goes, “Man, I really like the way that sounds. What are you doing next week? Do you want to do our next record?" And I’m like, "Sure!"

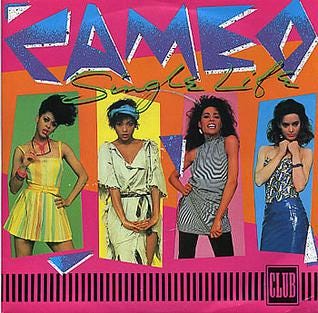

So after I'd spent a year or two at doing demos night and day, and tracks at Park South—along with a ton of commercials, which is a whole other connection—I went and did the Single Life album with Cameo. And that really launched—it all goes back to that day in that bar.

Then after that, I toured with them for a bit, then we did “Word Up,” and that was like the explosion. Then my career just took off because once “Word Up” came out everyone was like, “Oh, you gotta get that guy.”

But I can go back to that beer, that last five bucks. It all goes back to that day.

What an unbelievable story.

Yeah, I had also auditioned for Billy Idol. Which is a funny thing—this was the summer of '82 when I got off the road. I was on the road with Chubby Checker and I auditioned. And it was this thing where there were 100 guys, and I got a call back. Then there was 50, and I got a call back. Then there’s 25, and I get the call back. And this is going on over a month, you know, and they finally go, “Well, the original guy that we wanted to do it wants to do it. He turned it down [first], and so you're both going to come in. So we both come in, and then they tell me—of course, I hear the same thing—“Well, you played better than him, but we know him. We don't know you. So we're going to go with him.” And I was like, great. At that point it was still live drums, but after that they got into more machines.

(Editor’s note: The drummer in question in this case might have been Gregg Gerson, part of the original Billy Idol band. Gerson replaced drummer Steve Missal, and played with Idol through the recording of Rebel Yell, when he was replaced by Tommy Price.)

Everyone, I’m sure, wants to talk about the drums on the Word Up album. But I’m curious about the machines you used on Cameo’s Single Life?

That’s the LinnDrum and a Simmons SD5. Like, all those little white noises on “Single Life”—"chicka tackee”—that’s a Simmons, that’s all Simmons. Everything else was LinnDrum on that record. Straight LinnDrum, but I had this huge library of sounds. I would just get them all. I had a big box of chips; I had tons of chips. I knew that the sound thing was important, so I'd come in with, like, a million sounds. I still had my favorites. And then you had to lift the hood—you had to unscrew the thing, open it up, pop the shit out and pop one in and audition them.

By this point—1984, 1985—everybody is using drum machines. Can you talk about the attitudes about these things, especially as a drummer—that kind of shift that happened?

Other drummers’ attitudes? There’s a whole bunch of mixed things. You know who Allan Schwartzberg was? He was the guy. Jimmy [Bralower] did a lot more records than I did. I did a lot of records, but Jimmy did a ton. I also did a lot of commercials—five a day—and when I came in, Allan Schwartzberg was the guy.

He was doing all the jingles, and when it started to shift to the drum machines, a lot of the session guys really treated me badly. I mean, I remember one time, they're like, "You're taking money out of Allan's pocket!” I’m like, ‘No, Allan's taking money out of his own pocket.” Because he didn’t have a drum machine. And he even—one time I was programming it, and he tapped me on the shoulder and said, "You think I should get a drum machine?” I was like, “You better!”

But Jimmy and I, we saw it at the beginning. We were like, "I can be this guy. We can be these guys" and make it. Jimmy was the first one, I was like a month behind him or so, but I got to say, Jimmy was probably the first guy to go, like, this can be a session thing.

So I remember going to a session—it was a commercial, it was ten in the morning, and I walked in. And these guys knew me. There was a handful of the top session musicians in town. And so I walked in and walked over and started to talk to them, and all three of these guys just got up and walked away from me. They didn’t want anything to do with me. They felt that I was like messing up, because Schwartzberg—it was his thing.

But at the same time this is happening—you know who Neil Jason is? Bass player?

Yep.

Neil was my favorite bass player, and one of my favorite people in the world. He had just come up and got out of the elevator. And he saw me going over to talk to these guys and saw them just kind of walk away. And I was really new to the scene, and I was just, like, what the fuck did I do? And Neil came up to me and put his arm around me, and he goes, "Fuck those guys. You're on the A-team. They don't get it." And I’m forever grateful for him for that. He was forever welcoming me and telling me, you know, “Don’t worry about this shit. You’ll be fine.”

And so, there was like a bunch of guys—they were pissed!—because they had their club. And there were drummers who were, like, “Hey man, this isn't right.” And I’m like, “Yeah, it is right. It's what it is. It's part of technology. The guys from the Sixties, or the jazz guys from the Fifties, that didn’t convert into rock and roll, didn’t make it.

Meanwhile, guys like Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer—played on “Tutti Frutti,” Little Richard, he's the coolest guy in the world—anyway, [they] made the transition. {Palmer] was a jazz guy and became a rock drummer, he saw it coming. And then the guys from the Sixties that could play, they transitioned into the Seventies. There’s always guys taking over.

And Allan Schwartzberg gave me probably the best piece of advice anyone’s ever given to me. This is after I'd come in and kind of taken over for him—another thing where he tapped me on the shoulder. And he goes, “I’m going to give you a piece of advice, son.” Because he was a little older than me. He said, "You don’t own the chair. You only sit in it for a while." And I heard him. So I saved my money. And sure as shit, someone came and took the thing from me. That was Shawn Pelton, who came and took it from me. That's what happens. But I had, like, a ten-year run.

So there was a mixture of people...guys that seemed to stick around, and weren't worried about this club of session guys getting replaced, were cool with [drum machines]. And there were all kinds of guys that were open to it, because the smart guys saw that it was a part of what was happening, and you have to embrace it. It’s technology. You can't really fight it. You really need to embrace this stuff.

Drum machines could be a labor-saving device—especially considering how long it used to take to get live drum sounds. Was that part of the fast acceptance of the drum machine?

I think the main thing is it sounded different. It felt different. It could be a time-saving device. It could also be a time suck, where you’ve got all these options. "Hey Sam, you got snare drum sounds? Let me hear ‘em all." So, oh we got this, we've got that, we've got those options. Speed it up; slow it down. So you can get into the detail and the minutiae. And you know, at bar 57, why don't you do this little extra fill in there, now that now that we've got it all programmed? (Laughs)

As far as making time metronomic, it saved time in this way—as far as saying “This is perfect time.” But the weirdest thing about this, you know, was when I played drums, they wanted it to sound like a drum machine, and when I programmed a drum machine they wanted it to sound like I was playing live. And it’s still, to this day, when you’re live, it’s still like, “Oh, get it onto the grid.” And you play a drum machine, and it’s too stiff and too perfect. And so one of the things I embraced was being able to make the machine feel like I was playing it. It was more like a performance than just a static two-bar loop.

Whereas Jimmy was the king of finding--he could find the smallest two bars, and it would be perfect. And you're like, holy shit, I could listen to that the whole goddamn record. He’s amazing at stuff like that. And like I said, I’m probably his biggest fan. I want to feel more like [the drums are] moving around, you know, and he was trying to find that minimal thing. Which is just a whole different headspace—both equally important.

But I’d do a session where it was all day just to do drums, you know. Let’s just mess around—let’s work on the sound. Some of those guys gave me a lot of rope. They’re like, “Let’s experiment—we have all these options.”

What’s your philosophy about drum machines: make it sound like a real drummer, or make the machine do things a drummer couldn't?

It definitely varies. If I was trying to make it a sound like a live drum thing, then of course, you know, the crash—you’re not hitting it while you're doing a high-hat. Even now, look at Charlie Watts: when he plays a backbeat, there’s no high hat on it. It’s not because he can't do it: it's his choice. On the other hand, you may want a high hat—“I want this certain groove going and I want it to be nonstop,” so that it's just incessant.

Once I went in and played a groove for a record, and for the three-and-a half minutes, I didn't play any drum fills. I just the played groove. So I overdubbed toms. I could have said, “Oh, I’m going to play a fill here; a tom-tom here.” But I don’t want to pull away from the high-hat. It’s just a choice of what you want to do. And just because we're limited with four limbs, sometimes it sounds great like that, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Even when I have four limbs, I might just play kick and snare; I might not even play hat. I think it just comes down to a musical choice of what whoever is doing likes and what serves that song. That’s why drum machines don’t bother me. It never bothered me: it was all in service to the record, or to the commercial. It wasn’t about, I got a certain pride in being able to do things and make it sound live. When you play on a track, it’s one thing, and when you program a track, it's another thing.

And it's just, like, the bottom line at the end of day is, does it sound right for the record? Does it sound right for the commercial? Is that’s what musically pleasing, or musically what we wanted to do? And then the rest doesn't matter. What anybody else thinks about it, I wouldn’t give a shit.

Tune in for Part II of my interview with Sammy Merendino—coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com. And while you’re at it, check out Sammy Merendino’s website, as well!

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.