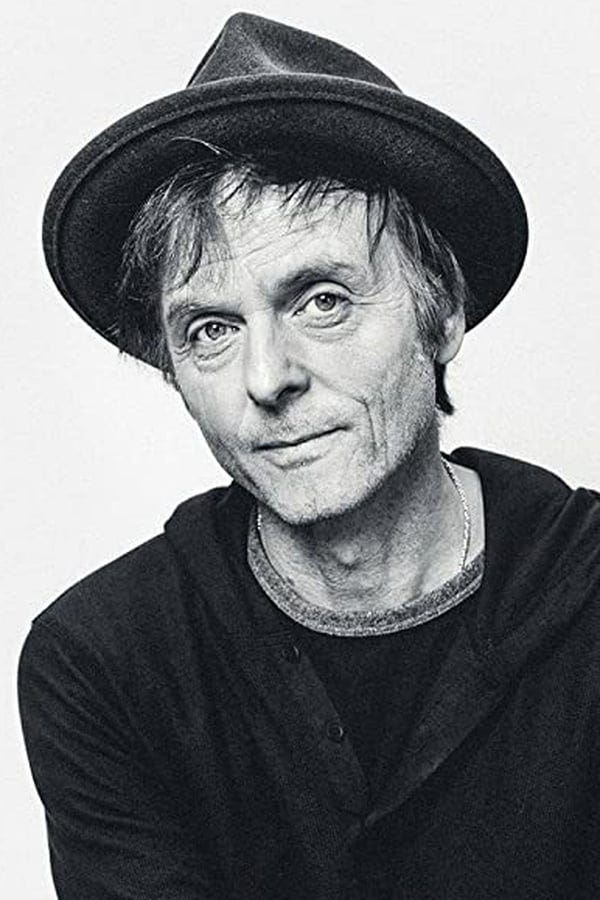

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT: An Interview with A-ha's Paul Waaktaar-Savoy

The best drum programmer you don't know...is actually someone you know very well indeed

If you ask people to name the top drum programmers in history, you’ll hear a series of familiar names. “The King,” Jimmy Bralower. Prince. Session pros like Sammy Merendino, John Robie, and Jason Miles. Pioneers like John Foxx and Martyn Ware, and masters of a single instrument, like Greg “Egyptian Lover” Broussard, the “king of the 808.” (Look for full interviews with several of the aforementioned folks, coming soon!)

A more surprising addition to the list might be Paul Waaktaar-Savoy. Not, however, because you don’t know his drum programming. As the principal songwriter and programmer in Norwegian trio A-ha, alongside singer Morten Harket and multi-instrumentalist Magne Furuholmen, Waaktaar-Savoy’s work has helped sell more than 50 million records worldwide. And it would be hard to find anyone who hasn't heard “Take On Me,” the band’s global Number One hit from 1985, and one of those rare songs that continues to resonate in the culture long after its initial release.

What most people don't realize is that Waaktaar-Savoy’s LinnDrum programming played a critical role in that song’s success. They also don't know that producer Alan Tarney insisted, years later, that “I’ve never seen anyone as good as him at programming a Linn.”

I caught up with Waaktaar-Savoy in early 2021, not long before the band began recording its eleventh studio album, True North. We talked about his drum machine history, both in and outside A-ha; his programming secrets; and the song he’s most proud of, drum programming-wise. (It’s probably not the one you think!)

One question I have been asking everyone for this book is whether they remember the first time they ever heard a drum machine — whether it was on a record, as part of someone’s home organ setup, in a music store, etc. Do you recall the first time you encountered one, and what your reaction was?

Yep, my first “band,” if you could call it that, was a joint venture with my best friend Ove, who had a Galanti organ with bass pedals and an internal drum box. Think cheese.

I was the drummer, and had to gone great lengths to make my own kit, due to lack of funds. We were probably 11 or 12 years old.

Speaking of pre-A-ha groups, I was listening to Vakenatt, from your old band Bridges. While it sounds like live drumming on most of the album, on the song “All the Planes That Come in on the Quiet”—which I think was revived in A-ha—it sounds like perhaps there is also a drum machine of some sort?

Towards the end of the Bridges, we wanted to shed a lot of our previous influences and fully embrace more of a synth-based approach. I traded in my glorious Gibson SG—from the Sixties, no less!—and bought a Roland GR300 guitar synth, which Magne called a 20,000 kroner fuzzbox. Ha ha.

We forced our drummer to buy the first electronic drums available, which he truly hated both the sound and playability of. I think they were called Syndrums. That’s what you hear on “All The Planes,” which was the last song we recorded for that album.

There also seems to be a fairly basic drum machine used on “Lesson One,” which would later become “Take On Me.”

On “Lesson One,” and also the very first A-ha demos, we used a Roland TR-55, which was the first drum machine I bought.

Somewhere I read that when you and Magne moved to London, you had to book sessions in a demo studio just to get access to a drum machine and synths. I wondered if this was John Ratcliff’s studio in Sydenham?

I also wondered if you remember what kind of drum machine the studio had, and if this was where you first learned to program one?

Yes, this was John Ratcliff’s Rendezvous. It had a LinnDrum and Prophet 5. Both amazing. The LinnDrum really made sense to me right from the get-go, and I quickly got super-comfortable programming it—which rarely happens, believe me.

One of the underlying themes among people I’ve spoken with is the skeptical attitude about drum machines and electronic percussion that existed in the music industry during the late 1970s/early 1980s. I think by the time A-ha formed, some of those attitudes had changed, but I wonder if you encountered them as well?

We spent no time thinking about that. Having spent most of our teenage years in rehearsal rooms, trying to get everyone to play well at the same time for a whole song or set, we embraced the new way of working with A-ha as more of a studio group, where every song had a different lineup and instrumentation.

I also felt I could get closer to the feel the song needed by programming the drums myself. But already on our second album, I started to miss some elements of live playing.

A lot has been written about the evolution of “Take On Me.” One of the things I find most interesting is that, according to Alan Tarney, he felt that the demo version recorded with John Ratcliff “was the hit version,” and the version recorded with producer Tony Mansfield had gone backward. There might be many reasons for this view, but I’m most curious about the drums on both versions.

Tony used a Fairlight for most of the drum sounds—maybe the Linn for the hi-hat now and then. It was a bit frustrating because we didn’t know how to use [the Fairlight], so everything would go through him.

It sounded more lumpy and less joyful—just repetitive. With Tarney, we went back to the LinnDrum.

Alan Tarney also said that you programmed his LinnDrum, and that “I've never seen anyone as good as him at programming a Linn.” In fact, the engineer Gerry Kitchingham added that it was unusual for Alan Tarney to let anyone else program drums: “Alan was a bit of a one‑man band, and he would program his own drums, but Pål was amazing. The fine details of his drum programming were brilliant.”

I’m curious as to whether you could talk about your programming technique and philosophy?

Most of the time, at least on “Take On Me,” I would program it imagining I’d be sitting behind a drum kit going for a great take…rarely repeating a pattern, and not putting in things that couldn’t be achieved with two hands and two feet. It was all about finding the right feel, making sure any fills or flourish wouldn’t stop the groove, but only add to the excitement. Tarney also had a trick of layering the sidestick with the snare that gave it nice “whack” on the song.

Warner Brothers tried to make us change the halftime feel in the middle of the choruses, but we refused, being our favorite bit—setting up Morten’s high note.

In the same piece cited above, I also read that you overdubbed live hi-hats and cymbals on “Take On Me.” Was this something you did elsewhere on the first album?

There were no live drums on “Take On Me”—all Linn.

On our next album, Scoundrel Days, we would add live drum elements on quite a few songs: “I’ve Been Losing You,” “Cry Wolf,” the title track, and others. Usually we’d program bass and snare drum, plus percussion sounds, and add live cymbals and fills.

“The Sun Always Shines on T.V.” is the other Alan Tarney production on the first album, and the drums are much bigger and more live-sounding than “Take On Me.” Is this a heavily processed LinnDrum? A Fairlight or Synclavier? Some other drum machine? A combination of all of the above?

This song is 100 percent Linn, and probably the one I’m most happy with, as drum programming goes. We actually didn’t use any sequencers in the early days. If you check out the demo of this song, the two synth basses are live, triggered by the cowbell and sidestick from the Linn.

This song—which was originally written as a ballad!—could easily have gotten way too frenetic, but the interplay of the hi-hat, cabasa, and tambourine keeps it cool. It was mixed on an old Neve board at Mayfair Studios that gave it nice, hard, but pleasing edge.

The drums on the rest of Hunting High and Low seem to be a mix of machines and Fairlight—which I assume was Tony Mansfield’s preferred setup. How much of the programming did you do?

Yes, mostly the Fairlight on that album—sometimes based on our demos and programming. Other times, [Tarney] would take it a different direction; compare, for example, the demo of “I Dream Myself Alive” to the album version.

Speaking of demos—many of which are included in the deluxe editions of the albums—they sometimes offer an opportunity to hear the programming that was later replaced by a live drummer.

I assume that a lot of the programming on these demos is yours, and I wonder if you could tell me, by the time of the second album, what drum machine(s) you were using to create demos?

All LinnDrum, but we constantly tried to find new ways to make it sound different—either by overdriving into a Space Echo or Effectron, or running it through a Bel Flanger they had at Rendezvous that sounded very good.

Adding the toms or conga sounds behind the snare and bass drum happened a lot, and every now and then we could use an 808.

Magne also gets drum programming credits on Scoundrel Days and Stay on These Roads. I assume this is because you guys both demoed songs, and that in at least some cases, the programming from your demos ended up on the record?

Yes, Magne did a great job programming the drums on the title track on Stay on these Roads. But by this point it was no longer a drum machine, but a Mac 2.

I read that the Yamaha RX-5 was used on at least a song or two on Stay on These Roads. While these machines don’t seem to have had the reputation as rhythm boxes like the Linn, the DMX, or the 808, I’ve talked to quite a few people who owned, and liked, Yamaha machines. I wondered which songs it was used on, and what you might remember about this machine?

By the third album, we tried a few like that one—for example, the percussion sounds on “Out of Blue Comes Green.” To me, it didn’t have the punch or the feel of the Linn, but we were ready for fresh sounds.

At some point during the late Eighties and early Nineties, standalone drum machines are largely absorbed by all-in-one samplers, and then by computers. I wondered when you officially made this switch?

By then, we’d started to miss playing live, and started focusing on capturing a great performance in the studio. So the fourth and fifth album was mostly all about that. Still, some songs retained a programmed feel—like, for example, “Sycamore Leaves.”

By then, I had switched to an Akai MPC60. That and the MPC3000 would be my main drum and sequencing tools throughout the Nineties.

Today, of course, you can get any drum machine sound you want via plug-in. There are still some people who swear by the old standalone units, however, for various reasons—sound quality, timing, the tactile experience. I wondered about your take on this hardware versus software question, regarding drum machines specifically. Is there still a place for the standalone drum machine? And do you still own one?

I hate programming drums with samples inside a computer. Just doesn’t give me any goosebumps. But it’s hard to go back to standalone machines, too, because the timing alway shifts when you print it. It never seems to be a straightforward process. Nowadays I use all hardware machines, but most of the time via MIDI or CV [control voltage].

I still use the Linn, but also a Drumtraks, a DMX, a Pulsar23, a Vermona, the Elektron, DFAM, the Roland TR-66—or sounds from modular synths.

While I know judging something like this is highly relative, I wondered who the best drum programmer you’ve ever seen (or heard) is? You can, of course, vote for yourself!

Ah man, there are so many cool ones. It doesn’t have to be fancy or tricky in any way, either, for me to like it!

Tune in for more full interviews with the pioneers of drum machines, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.