He Put the Word in "Word Up!"

Part II of a conversation with Sammy Merendino, drum programmer extraordinaire

As a drummer, Sammy Merendino is a certified A-lister—a first-call session man who’s played with Michael Jackson, Aretha Franklin, The Beach Boys, and Billy Joel, among dozens of Rock & Roll Hall of Famers. But as a drum programmer, he was a member of an even more rarified group. During the Eighties, only Jimmy Bralower, the “King” of drum machines, could match the requests for Meredino’s programming prowess.

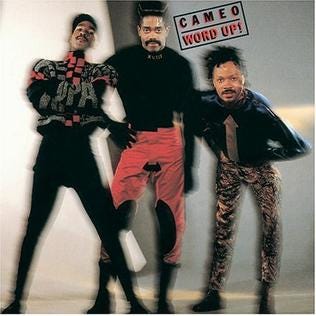

And perhaps the pinnacle of Merendino’s drum machine odyssey was his work on Cameo’s massive 1986 album Word Up! The title song became the R&B group’s biggest hit, and the drum sound of that record—including the follow-up single, “Candy”—was imitated for years afterward.

I was fortunate enough to speak with Meredino for my book Dancing to the Drum Machine, the first real history of that controversial instrument. In Part II of my exclusive conversation with Merendino, he discusses the origins of that iconic Cameo sound, as well as the guts of his custom drum rigs, and why he prefers drum machines to plug-ins.

The Eighties were the time for snare sounds, and one of the most iconic snare sounds comes from a record you played on, Cameo’s 1986 hit “Word Up!” What was the programming setup for that song?

That record was a real collaboration, first and foremost, Larry Blackmon had the vision. I gotta give Larry the vision credit for this. Larry is an incredible drummer. I was so fortunate to spend time with him, I learned really a lot from Larry. We hit it off, he and I just had this thing where it just worked.

So I’d done [the 1985 album] Single Life, and we'd toured over in England. And on the way back from England, he told me, “This next record is gonna be big.” He goes, “I already hear it. I know how the business works.” He’d figured out how the whole payola thing worked. And he had been going and doing all these promos in England—he'd go to all these pirate stations where they had to blindfold you and take you all around town, so you didn't know where they were [located]. It was a wild thing.

So we go in this studio, and Larry says to me, "There’s going to be no reverb on this record.” And I say, "What?" He says, "No reverb!” And he actually fired an engineer who put reverb on something, because he’d told him a couple times not to do it, and he kept doing it—he fired him, you know. Cause I even asked him if I could have a little [reverb]. He said, “Nope, the sound of this record is going to be in your face. Tight. It’s gonna be drums, so up front.”

So at that point, my setup had expanded because I used to buy—I used to have standing orders at Manny’s [Music, in New York City]. It was like, whatever new comes in, I’ll buy it. Just give it to me. I didn’t care what— whatever it costs, I want it. So I would always get the first everything that came in. [Drum programmer] Jimmy [Bralower] was like that too. Jimmy was like, “Stay on top of this stuff.” I remember buying drum machines, the Sequential [Circuits] ones, and I’d be like, “Yeah, I don’t need this.” I would just sell it for whatever. But I had to take a chance on that stuff.

So by the time we got to Single Life, I had this massive rig. Do you know who Vince Gutman is? Vince had a company called Marc, and he made triggers—trigger boxes. And he was this savant tech guy. He could build anything. He lived in Chicago, and he was building custom racks for people. So Jimmy had one. I had one built. You'd send all your gear out to Chicago, or you'd send the bulk of it, and he'd fix and rewire it so that when you plugged it in, it sounded great.

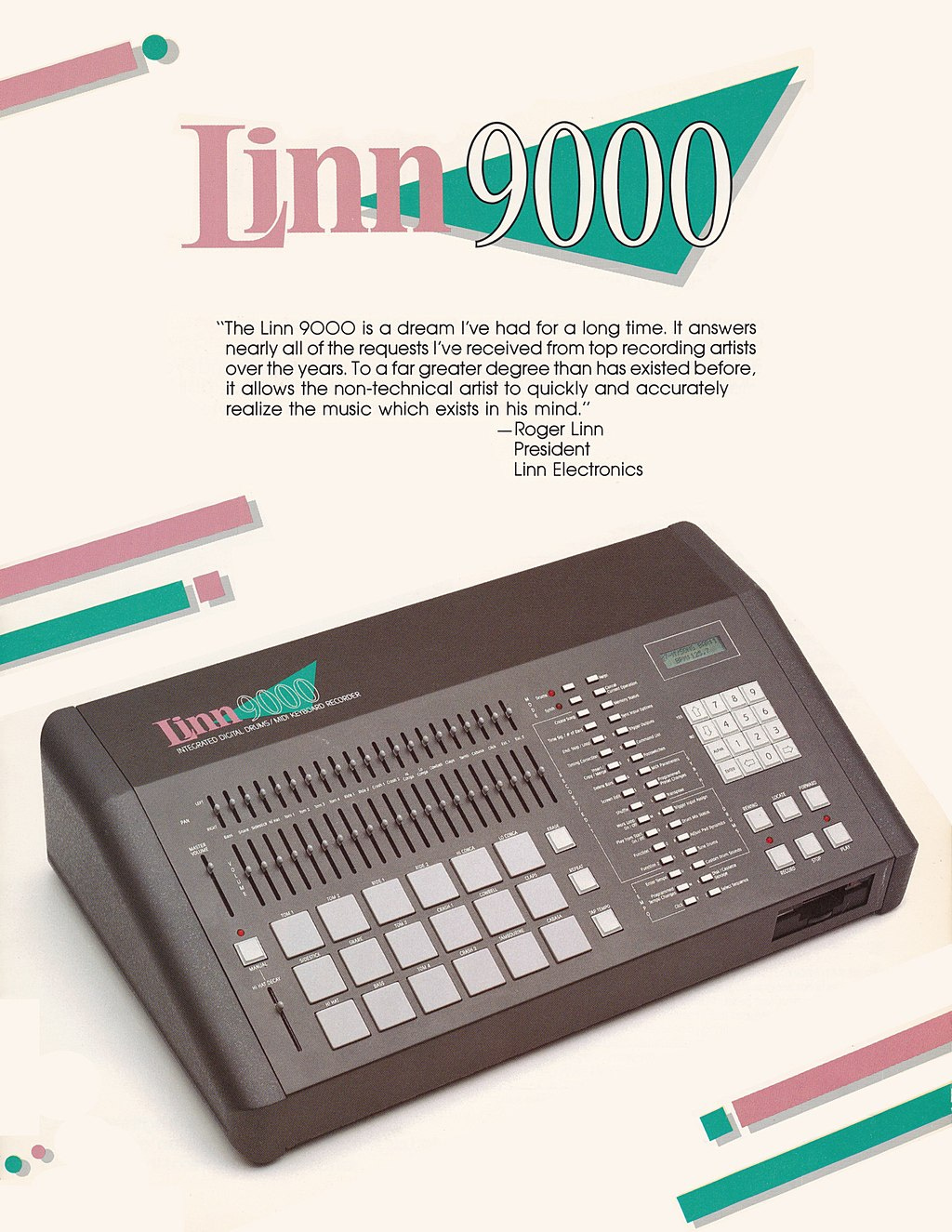

So at this point I was running a Linn 9000, a couple of Akai S900s, a Simmons SDS5, a Simmons SDS7, and a rack with mixers, reverbs, gates, compressors—I had, like, this massive rack. I had this computer, a Macintosh, with Sound Designer. At the time, it was the first pre-stereo Protools. And at that point, I was making my own samples. So I was recording everything, and I wanted to make sure that the [samples] were all truncated right. So basically, I remember buying a hard drive for, like, 3,000 bucks to store this stuff on, like, 100 [MBs]. It was three grand so I didn’t have to use floppies. So I had this massive thing with one of the first Macs—it was a "Mac in the rack,” we'd call it. Vince did all that stuff for me. So when I’d walk into a session and bring my stuff in, it was just spotless, quiet, perfect, I even had all my own cables, I had everything.

So back to the sound of that record. The bass drum—I had made that bass drum at Media Sound, that sound for the bass drum. It was actually two: it was the Linn—the stock Linn 9000 bass drum, which I think is from the LM-1 or [Linn Drum]. But I had made this bass drum with one of my bass drums, too. When I first got the sampling card—which was like an additional thing on a 9000—I had never sampled anything. So we took the feed, and we recorded some bass drums there on tape. And then I fed it into the machine and I overloaded the machine, the samples—the first sample I ever made. And it was that "kshhh" on that bass drum. And my friend is like, “It's all destroyed,” and I go, “Ah, I’m gonna keep it. I'll use it for something someday.” So I just stored it and put it away.

So when we're doing “Word Up!” Larry’s like, “Well, we kind of want the “Single Life” thing, but we wanna make it bigger.” So I can’t remember—the snare was either number 12 or 14 in the library that was the “Single Life snare.” And I had this bass drum with the other [bass drum], and it was all kinda working. But Larry was like, “Y’know, the snare drum not right yet.” So we were at Quad Studios in New York, which was on 7th Avenue, between 48th and 49th—it’s gone now. I think it was the 11th floor. Eric Calvi was the engineer who was instrumental in that snare sound. There was this huge stairwell that went all the way downstairs. So we recorded Larry clapping his hands in that hallway into an AMS [RMX16 digital reverb], and then we laid that on top of all the other snares--on “Candy” and onto “Word Up!” So it was just a hair of the old “Single Life snare,” but mostly this handclap through the AMS. It was just immediate: between that bass drum and the snare, it was just that big low-high contrast, and it became a signature thing for Larry, and it was this massive sound.

“It’s the only perfect record that I’ve ever done. ‘Word Up! and ‘Candy’—I wouldn’t change one single thing. It’s the only thing I’ve ever done in my life where I wouldn't change anything.

—Sammy Merendino, about the Cameo album Word Up!

And then there was some other stuff. In “Candy,” there's that kind of gated cowbell sound I was using, this metallic thing. And I also took the “Single Life” noises, but [put them in] an SDS7, where I could really filter that stuff around. So I would just play those sounds. If you listen to those, it's kind of a linear pattern—those kind of fall in and out of the hi-hat and the kicks and the snares. So if you listen, it kind of fills in the gaps. When I did “Single Life,” wherever there was a little space, I put in that little white noise or that “takita" sound.

It was an awesome time. The weird thing is, all those things just flowed. I’ve been trying to get back to that point—I’ve always been trying to get back to that point in my life, musically and mentally and emotionally. It was just, like, we did that whole record in a week, maybe 10 days, as far as drums and stuff. It just all came out; there was no real problem doing it... it was probably the easiest record I’ve made in my life. It's probably the closest thing to perfection—I’ll rephrase that: it’s the only perfect record that I’ve ever done. “Word Up!” and “Candy”—I wouldn’t change one single thing. It’s the only thing I’ve ever done in my life where I wouldn't change anything.

And I was thinking, like, “Well, how can I get back to that kind of thing?” You know, I get close to it sometimes. But it was just an amazing moment where like everything aligned, and it was awesome.

You mentioned the Linn 9000, which really seems to have been a polarizing instrument. Everyone I’ve talked to seems to have loved them or hated them—sometimes both at once!

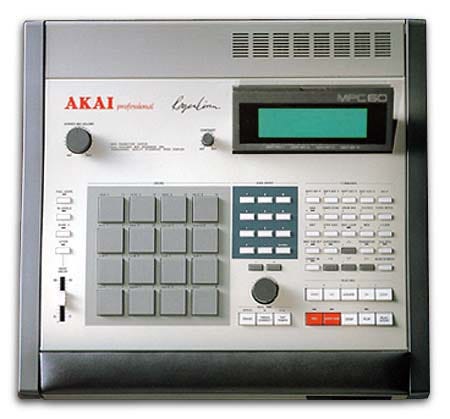

Well, I had three of them, basically because of the reliability thing. I was like the guy who has all the cars in his front yard—he’s always taking the starter out of one, putting it in the other. I was always taking parts out of one to fix the other one. I didn't even bother putting the screws in the Linn because I was always opening it up and jiggling stuff. That was the downfall of Linn, unfortunately. Then the Forat brothers came in and kind of fixed it up a lot. But for me—I know Jimmy [Bralower]’s thing was more Akai. He loved the MPC. I loved the Linn 9000: it just felt more organic and analog to me.

Ae of the reasons was that we had it measured. I had this Russian Dragon [a device that measured rhythmic accuracy], and the MPC is much more accurate, as far as where it places beats. Every bar is the same. The Linn, everything is serial—the way it feeds the MIDI information.

[Editor’s note: this reference to “serial” essentially means that some electronic devices, like drum machines, reproduce sounds in the “serial” order their keys or pads are struck—even if the keys seem to be struck at exactly the same time.]

So if a bass drum and a snare drum hit at the same time, they don’t really hit at the same time. The bass drum goes first, and then the snare is second. So there’s a little bit of a delay there. And so if you stacked up certain things—if you're playing kick, snare, hat, those things had to hit before the next thing would happen. And the clock wasn't quite as accurate, and so it tended to move around a little bit, which I found awesome—because then it felt to me more alive. It didn’t feel rigid to me.

But there'd be times when I'd be working on it, and it would freeze up and I'd lose everything. But to me, it was worth it. I remember I even had a MPC I threw across the room once, because it froze up right in the middle of a session, and I was pissed. I tossed it across the room. My friend caught it by the power cord. He laughs about it to this day.

The Linn, to me, it just had this feel that I loved. When I had my Akai, which I used more on the third Cameo record [1988’s Machismo], it feels a little different. I really think what I loved about “Word Up!” was that it wasn’t perfect. Even though it was a machine, it felt more human to me than the other records, and that was based on the 9000. Sonically it didn’t sound human, but feel-wise, it did.

But they're great machines. Right now, I have an MPC Studio that I use with my Pro Tools, and I have that sitting on my desk. My Linns are long gone—by the time I got done, I had kind of burnt out on programming and went back to playing more live stuff. And at that point, the Linns were so beat up. They're all great [machines]—they just have specific things that they do. It’s like a Les Paul and a Strat.

At what point did you make the transition away from the standalone drum machine?

I always carried external samplers. The MP60, that was only 12-bit, which was cool. I had this Forat sampler [the F-16] that was 16-bit. Larry [Blackmon] hated it. It was too clean. Larry liked the graininess of the 12-bit samplers, the cheaper samplers. So part of my rig was, I had my S900. When the Akai MPC60 and the 3000 came out, I’m not sure if that was 16 bit or not, I think it might have been. [Editor’s note: the MPC60 was 12-bit; the 3000 was 16-bit.]

I had a few E3XP [samplers]; they were called Emulators, and those sounded good to me. And you could put a lot of memory in them—that was another thing, the memory. You could fit so much inside the MPC. And I would hire out Atlantic studios, or go to a big studio somewhere, and record drums for the day, and have all my own samples. Like, I'd have stereo cymbals, and I'd have room sounds for the cymbals and room sounds for the drums, and everything was imaged where it’s supposed to be. And my cymbals were, like, 17 seconds long, and then they were stereo. So you couldn’t fit all of that into a drum machine.

So I never really went away from that. I always had my external samples, until I decided I wasn’t going to program anymore, and I kind of hit a wall, and was like, “I don’t really want to program anymore.” I was like, “I want to play drums again.” I got tired of being—people also forgot that I was a drummer. And then people wouldn’t really hire me to play drums anymore. They only hired me to program. They'd be, like, “Well, you program—you can’t play drums.” And I’m like, yeah, I can.

When you got a call for a session, was it apparent whether you were going to drum or program?

Well occasionally I'd have Simmons pads and I'd overdub—like on Foreigner [the 1987 album Inside Information], I overdubbed some tom fills. And there’s a record [session drummer] Steve Ferrone wouldn’t play on, so I had to play tom fills. I sampled his things and played them in. But I was getting calls mostly as a programmer, and the thing was, I was getting paid double scale as a programmer and single scale as a player. So I was like, “Yeah, I'll program.” And plus it was Jimmy [Bralower] and I [who] had that [programming] so locked up. I was like, yeah, I’m going to keep this.

I mean, I was turning down $100,000 a year in work. I mean it. There was just so much work, there really was not time to play. I mean, there was a five-year period where I did not pick up a stick. I didn’t touch a drumstick. I think it was after “Word Up,” from, like, ’85 to ’90, I’d say, I didn’t even touch a drumstick. Everything was on a pad. Every single thing was on a pad. Sometimes I’d play fills live on top of something, but generally at that point, I was just, like, “Let me program it—it sounds fine.” So my call was almost always [programming].

And like I was saying earlier, [session drummer Shawn] Pelton came in, and people started to get away from the drum machine thing then. That was around probably around ’92, I’d say. At that point, it was starting to slow down. People were like, “We kind of want live guys again.” It just turned the corner. And so I kept going, but I could see that my career was starting to come down a bit. And so then, by, like, '95 it was like, yeah, you need to start practicing again. It was half out of need. It was like seeing it come in—you also have to see when something’s going out. A lot of guys got stuck in what they were doing, so there were a lot of them at that point who were still programming, who weren’t thinking about seeing the change again. So fortunately I was like, “Yeah, I better start practicing, so that I can play live again.” Because you don’t own that chair: you only sit in it for a while.

What was the record you just mentioned where you had to overdub tom fills for Steve Ferrone?

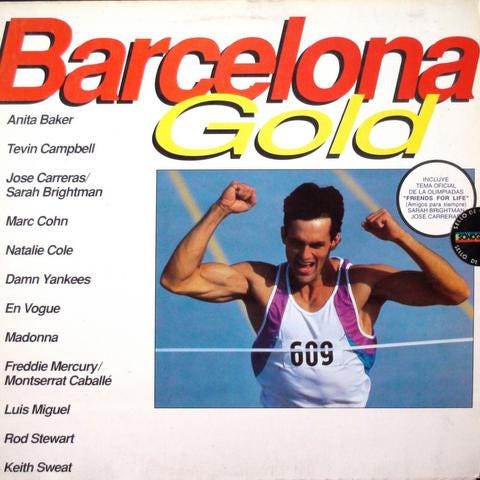

It was an Anita Baker record. It was for an Olympic thing—I think it was called “How Fast, How Far.” And it was funny, because Barry Eastmond was the producer and the writer, and he worked a lot with her, so he called me in and Steve—probably one of my top five drummers ever. I love the way Steve plays.

So Steve does that sixteenth-note [hi-hat] thing with his right hand, you know, and the reason I think he didn’t do a fill was because…losing the hi-hat on the fill, it kind of broke the momentum of the song. So I understand why he didn’t play any fills. But it was funny because they cut the track, and they were like, “When we get to the chorus, can you do a fill?” And he’s like, “Yeah, I can do that, man, no problem.” So they do another take—same thing. He wouldn’t play a fucking fill. They’re like, “Hey Steve, that's really fucking great. Next time, we really need a fill.” And he’s like, “Yeah, I can do that, man.” They played it, like, three or four more times. He'd tell them yes, and then he wouldn’t do it.

So there was another song where he had played a tom fill to start a song. And I went in and sampled the toms, and I went in and played the drum fills on top of him. To me that shows you just how heavy he is: that he can go “Yeah” and then not do it—and they’re still cool with it.

You were just talking about your custom rigs. What was the setup you used for Cameo?

Playing live, you mean? Yeah, when I played with Cameo, it was just a real kick and snare, and then all Simmons toms. And then a Linn Drum to my left for when played “Single Life,” but it was still a real kick and snare on that for the live thing.

Speaking of playing live, lots of folks I’ve talked to for this book have shared their drum machine horror stories from gigs. Do you have any?

To be honest with you, I didn’t have any. And Jimmy and I laugh about this: we always say, “How come people have so many problems with these things?” I have had no problems live with drum machines. It's like, I read the manual. And I also carried backups, so if a machine would die—my worst horror story is, like, “The machine’s dead. Put the other one up.” Because it was just about being prepared, and so I just didn’t have any of those problems. Other people did, and I don’t know why it was so hard for people. But especially if you have Vince Gutman working on your rig, it was pretty rock solid. He would wire everything up and make sure— he'd open up the machines and make sure things were right inside the Simmons and everything.

So if you spend the money and the time and you read the manual—it’s just when you learn how to do that stuff, you don’t have problems. And that’s why Jimmy and I managed to have careers out of those things. And it was a career: it wasn’t just doing it on the side; it became a career of its own.

“So the MPC that’s in the computer—it’s like an MPC, but it’s not an MPC. It’s like it. I don’t want like it. I want it.”

Do you think plug-ins will ever replace devices like drum machines?

I guess if I’m listening to my MPC Studio here, it feels a lot to me like an MPC. What it doesn’t do—the MPC was 12-bit, but I guess they have one called the Renaissance, where you can actually go into the old mode, and it gives you the grainier sampling sound. Plus you're taking the cable out of your machine into the mic pre, and then it goes into whatever you're recording. So that changes a lot of stuff—that right there toughens it up. It’s the same as using EQ.

So the MPC that’s in the computer—it’s like an MPC, but it’s not an MPC. It’s like it. I don’t want like it. I want it.

If I was going to get back into programming again, I would get a drum machine. I’d have them both so I could use either one. But I’d say yeah, I prefer the machine, just because my hands on are it. I never liked programming on a piano keyboard. I like pads: I want something that I’m hitting. Keyboards are for pianos and organs and synths. Because of the drums, it needs to be a pad. It’s a different attitude.

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com. And while you’re at it, check out Sammy Merendino’s website, as well!

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.