If you talk to the pioneers of drum machine use, you can expect to hear some horror stories.

Not just the time the machine dumped its memory right in the middle of an important session, but the time someone had to adjust a tempo knob manually throughout a song to get the drums to sync to a bassline. Or the time someone had to manually punch buttons to “play” a drum part for six, seven, or eight minutes—maybe even longer.

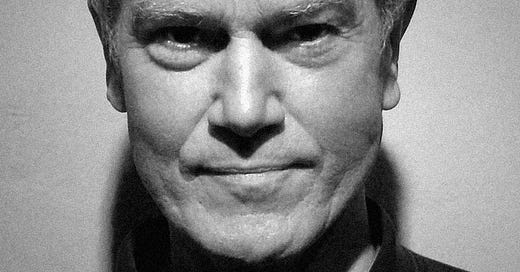

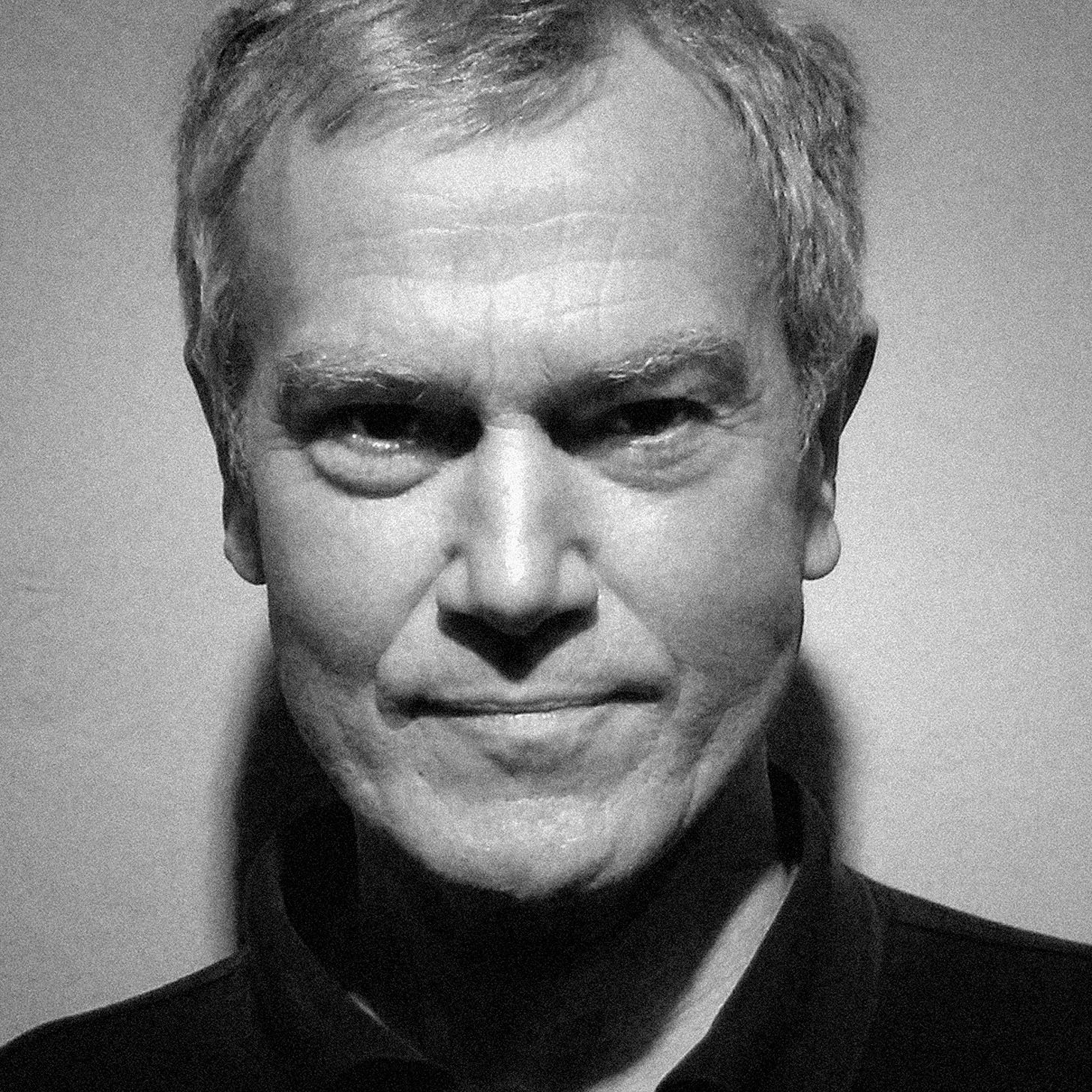

In short, it took a lot of optimism to be one of those pioneers. And there might not be a better example than John Foxx.

Foxx not only paved the way for generations of drum machine users, thanks to his early adoption of rhythm boxes as the frontman of new wave titans Ultravox, and in his enormously influential solo career. He did it while retaining a “joy” in programmed rhythm that has survived to the present day.

“I loved the strange sounds and feel of the machine,” says Foxx. “They were entirely new at the time and felt uniquely stark and alien. I really loved investigating all this.”

These days, Foxx burnishes his credentials as a true Renaissance man: he’s an author, a visual artist, and a filmmaker. But he continues to add to a discography that encompasses minimalistic synth-pop, evocative ambient music, and analog electro-rock—the brief of John Foxx and the Maths, a group that includes Foxx’s fellow drum machine enthusiast Benge.

In Part I of my conversation with Foxx for the book Dancing to the Drum Machine: How Electronic Percussion Conquered the World, we talk—among other things—about Ultravox’s groundbreaking drum machine experiments, the prescience of Brian Eno, and what it means to be “phased, flanged, and fucked.”

In lots and lots of interviews over the years, you have said something that I love (I always tell it to my students): that limitations provide a sort of freedom; that too many choices can destroy creativity; that working within restrictions opens up possibilities we wouldn't have considered otherwise.

In some cases, you were talking about drum machines, and in others, you were speaking more generally. I wondered first of all whether you still feel the same way about drum machines—especially in an age where we can sample them and then open them up to nearly limitless digital variations.

Still as vital as ever. These things don’t change. Having the possibilities of an infinite range of drum machines—or any other instrument or technique, in any medium—simply begs blandness.

Even imperfect things are useful. My advice to anyone making electronic music would be to seek one out and make it your own. Getting deep into a single machine will provide identity and help mark out your own unique territory.

How important does the restriction of working with a physical device remain to you as a composer and artist?

The joy of primitive machines lies almost completely in their imperfections and limitations—these invite you to use them ingeniously, in ways they were not designed to operate.

For instance, distortion is as useful as it has become to guitars. New and old guitar effects pedals, applied to synths and drum machines, will give various fascinating sonic signatures—flanging, phasing, echoes, reverbs, loopers, a pleasure in extraneous noise, gating, manual switching, earth buzz, going through valve amps, dubbing in the mix, radical stereo separation, adding synth generated percussion noises manually, and using echoes to add extra rhythms—all these and many other physical interventions become available.

Imperfection is character, becomes identity and adds fascination.

In Ultravox, you were working with Brian Eno at roughly the same time he was beginning the Berlin trilogy with David Bowie and Tony Visconti. Even though there aren't a lot of drum machines on those three Bowie records, I’m curious specifically about the influence of the drum sounds on those albums—especially the “gorilla” snare sound that Visconti developed using a harmonizer—on Ultravox, and your early solo career.

Well, we’d already recorded the first album just before Bowie called Brian to work with him for the first time. We were actually mixing it in the studio.

I didn’t get around to using a harmonizer for some years after that , simply because they were far too expensive then. Anyhow, I much preferred the sounds from guitar pedals as effects, because they had the ferocity I wanted.

Brian was an extraordinarily prescient character. He’d been using a drum machine on Another Green World, and for me, that was a real breakthrough.

It acknowledged the joy of artificiality as a valid element of recording, rather than this dominant pretense of “authenticity,” which was thought to be justified by recording “real” instruments.

Even though these were all becoming mutated into ciphers of their former selves, through the use of studio isolation, compression, equalization etc., and by the new separation facilities of multitrack recording. By these means, all instruments were incrementally beginning to sound completely unlike the original source sounds.

As an example—this tendency was especially marked in the sound of electric guitar—which, by 1976, bore no resemblance whatsoever to the acoustic instrument of its origin. After long mutation through the adoption of steel strings and solid-bodied instruments relying entirely on electronic pickups, valves, then the introduction of amplification and distortion etc., the guitar came to function as a low animal growl or a mutated cross between a howl and a violin, and this had become an unquestioned, conventional sound demanded by engineers and audiences.

No one but Brian and a few others seemed aware of the unexamined, inexorable assumption that this strange, unquestioned acceptance of artifice now represented ‘authenticity’.

The problem for artists was: the propagators of this convention seemed unaware of their acceptance of it, and affected to despise other modes of sonic artifice as ‘“inauthentic.” So it was all becoming a bit daft.

Meanwhile, a similar thing was happening to recorded drums—compression, isolation and separation had allowed a totally functional and powerful sound to emerge, but it was also completely unrealistic.

This sound was created almost entirely by electronic processing. The source, the acoustic drums, ended up acting as a trigger and injecting a few useful frequencies. Even the dynamics tended to become flattened by compression.

Again, this incremental path to artifice was barely noticed, even by all the engineers and producers who’d created it. The synthesizer and the drum machine were obviously the next stage in this evolution.

Drum machines eventually took those all processed sounds as the norm, rendered even more artificial drum and percussion sounds via analogue synthesis, then allied them to a sequencer/computer, so they could be metronomically reliable. One of their great advantages was they also took no time at all to set up and deliver a workable sound in a studio.

In an interview from a few years back, you mentioned that Eno’s use of a drum machine on Another Green World was influential—and that you had used “a previous cocktail-lounge machine” on the first Ultravox record. I was trying to figure out which song (or songs) used the machine—do you recall? And was it the Roland TR-77, or another unit?

We certainly had a similar cocktail rhythm box in the studio when we did “My Sex”—that was in September 1976, so it must have been a forerunner of the TR-77.

I remember my idea for that track was to record a real heartbeat, which we tried, but this didn’t quite work because it was too muffled, so we then used a bass drum from a previous recording that Brian had made, but I seem to remember this wasn’t the right speed or rhythm, so we may well have used that machines bass drum in the end.

Later on, we also used to get a nice, powerful bass drum and snare sound using the ARP. Later, the drum and percussion sounds on “Dislocation” particularly, were done in that way. I also made many of the percussion sounds on Metamatic using the ARP.

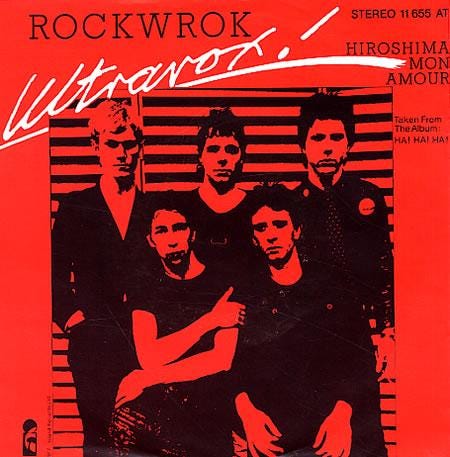

“Hiroshima Mon Amour” is usually described as Ultravox’s first “drum machine” song. But were there any other songs on Ha!-Ha!-Ha! where you’d experimented with it? And how important was the machine itself (assuming, of course, that it was) to the composition of “Hiroshima”?

I wrote several of the songs on that album using the drum machine. I’d write the songs at home, then we’d lay real drums over that in the recording. There are probably drum machine tracks on the masters which were initially used as a click track or guide.

After working at home with the TR-77, I’d begun to realize that real drums were no longer what I wanted to hear. Real drums took ages to set up and record. A band would easily spend at least one or two entire days getting a workable drum sound. With the drum machine you simply plug it in and off you go.

I loved the strange sounds and feel of the machine. They were entirely new at the time and felt uniquely stark and alien. I really loved investigating all this. Writing songs and playing along to those loop patterns also lends a very different feel to everything you record and write. It can provide clipped power or trance-like hypnotic rhythms.

This became particularly obvious during the writing of “Hiroshima,” where the drum machine actually set the mood for the entire piece. In fact, I always felt it became the lead instrument for the song.

Also because the original [Roland] CR-78 and TR-77 had mono outputs, you can abstract the sound even more by hooking the machine up to a flanger or phaser, intended as guitar pedals, and you can also mutate the actual rhythm through repeats on a space echo. It was also possible to work live with this. The idea was always to push the sounds as far as possible using any available means.

It’s maybe worth looking at the realities of recording in those days. In 1976/7 a studio would cost around £1,000 for each day, then you had to pay equipment transport, crew, hire costs, etc. on top.

Worst of all, though, getting a good recorded drum sound was a long and tedious process. Often the rest of the band might have to kick their heels for a day or more, and this leached the energy right out of the session. You can’t make exciting music when you’re bored to death. Also, even after enduring all that, you ended up sounding just like everyone else.

I always felt that real drums were such a cliché, when there were many other sounds that could be generated by synths and machines that could be much more powerful and interesting. A drum machine seemed to offer the solution—switch it on, and off you go. A liberation from exhausting days of energy absorbing tosh, and vast potential for further sonic mutation.

In 1977 I wrote “Hiroshima” at home using the TR-77 (which I’d bought by that time), then as usual, we recorded the song, leaving the drum machine off the track. After some consideration, I realized I wasn’t happy with that initial recording, so brought us all back into the studio and played the version of the song I had in my head to everyone, over the TR-77 rhythm. The TR-77 certainly set the entire mood and atmosphere for the piece.

During the “Hiroshima” session, we used the simple technique of punching in extra presets and instruments. We also found the drum machine could play a couple of presets at once—it was limited, but could be extremely variable if you explored it thoroughly. Warren enjoyed this and took to punching sounds in and out live as we recorded.

Warren was a precise drummer, and turned out to be good at synchronizing himself with machines. He grew to enjoy the process and, coupled with the use of raw synthesizers, I began to realize this gave the band a different sound and feel.

This helped trigger me into writing very different songs and modes to accommodate and explore it—enabling us to sound completely unlike everyone else at the time. The curve of that Ha-Ha-Ha album perfectly illustrates the discoveries we were making and consolidating then—it goes from the violent feedback, which we were leaving behind, right over to “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” the last song on the album and the distinct signpost for the future.

There’s an alternate version of “Hiroshima” that features live drumming. I wondered which version came first, and whether the fact that there are two versions speaks to any doubts about the use of the drum machine?

I think the conventional one was recorded first, but that came after I’d initially written the song at home using the TR-77. After I listened to it for a while, I realized how we should record it—as written. So I called everyone and we went back into the studio and did it in a couple of hours.

Warren Cann seems to have adapted pretty quickly to the idea of drum machines; I have read some interviews where he talks about the very precise mods he made to the Roland TR-77. What was the attitude of the rest of the band about this shift?

I think everyone realized it was a good thing, and it fitted perfectly with the shift we were making into using synthesizers.

The song “Quiet Men” seems like a turning point. You still play it, you’ve written a book of short stories that borrows the title, and the idea of the “Quiet Man” has been described as the backbone of many of your lyrical ideas during your solo career, as well as other art projects.

In contrasting that song with “Slow Motion” on Systems of Romance, though, it really seems like here were two directions Ultravox could have gone. And you chose the second one—which, for the purposes of this discussion, also included a drum machine, and a spare sound more closely aligned to your first solo album, Metamatic.

I wondered if that seems a fair assessment of how you viewed things at the time?

Yes, it does. I was very aware of the two alternatives. In Systems, we’d made a blueprint which we knew was the way to go from then on. Then I left the band and in doing so, left that particular field open for everyone else.

Almost every other band of that generation quickly adopted that blueprint, to some extent—guitars with effects as an intrinsic part of the sound and drum machines with real drums and synths—Simple Minds, U2, New Order, and the second version of Ultravox, etc.—and they were all commercially successful with it.

By the end of 1977, I’d already realized I didn’t want to be in a touring rock band at all—wasn’t cut out for it, so I headed into a much more risky territory, but one I was far more comfortable with. A more completely electronic sound with no real drums or guitar.

I could stay in the studio and make experiments. That was how I felt. I knew the other bands would most likely be successful but it wasn’t a way of life I ever wanted.

When you left Ultravox, it was at a pretty auspicious moment, technology-wise. You stated, a few years later, that “I wanted Metamatic to be the first all-electronic album, because I knew it would be.” I assume that at least some of your thinking in departing the group was based on that technology—that it would allow you to do what you did on Metamatic?

Exactly. I realized I’d have to rethink popular music from the ground up. You had to do that if you wanted to use synths instead of conventional instruments; you had to understand all the normal layout of bass, drums, lead melodies, chords, vocals, etc., and reconsider every last bit of it. But you couldn’t easily do that with a band.

And then it would have been difficult to play live and tour—and it might not have worked out financially enough to keep a band together.

As a small, mobile unit of one, I was free to follow my instincts, without too much risk and without the constant justifications you need to come up with in a band.

At that point, I needed minimal simplicity, in order to throw everything out—then rethink and redesign everything from the ground up, in the light of what these new machines could do. It was fascinating.

How radical this process actually was, went completely unrecognized at the time, though. I remember Peter Gabriel announcing, as a deeply radical move, that he’d done an album without cymbals. (Editor’s note: this is a reference to Gabriel’s third solo album, released in 1980—around the same time as Foxx’s Metamatic.) I thought, “Well, I’ve just done an album with no real drums at all—and no ‘real’ instruments either.”

Much later, I also remember when Prince was lauded for doing “When Doves Cry” without a bass—I’d done that some years before, with several tracks on Metamatic. I realized tuned drums and re-equalized synth could sometimes supply all the bass needed and leave the track more agile.

You have said that the Roland CR-78 was the first drum machine you bought yourself, sometime in 1978. I was wondering how much you still recall about the actual purchase: where and when, exactly, you bought it, and how much you paid? What happened the first time you switched it on at home and started trying to use it? How you figured out how to make modifications to the rhythms, and how long you'd had the machine before you did this?

I’d actually had the TR-77 first. I remember getting Warren to come around to my flat and checking it out with him, before we recorded Hiroshima again. I didn’t want any adverse reaction in the studio.

To his credit, he enjoyed using it right from that moment. That was in early 1977.

I’d previously discovered you could add and subtract parts and push two rhythms in together. I always had a policy of taking every piece of equipment as far as possible, and beyond, simply to see what might happen. It was all very simple and primitive of course, but it was a new sound and that’s what we were after.

I loved using it at home, putting it through a guitar amp, which made it nice and pokey. I immediately wrote “Hiroshima” using that machine. I also used it to write “The Man Who Dies Every Day” and “Artificial Life.”

A year or so later, I bought the CR-78 from some music shop on Sunset Strip in L.A., just before I left the band. I also bought an MXR Flanger/Doubler at Manny’s in New York, which got used on almost everything on Metamatic, especially the CR-78. I really can’t remember what I paid, but equipment was much less expensive in America then.

I do remember declaring these things at UK customs, but they let me off paying any duty for them. The CR-78 had a little programmer which I’ve still got. Hard to use but it meant you could sometimes customize the basic drum pattern.

I always found that machine an inspiration—the sounds were so alien and the rhythms so strange, they were absolutely perfect for the feel of Metamatic. Especially when we put the MXR in. It was a weird, icy but somehow organic sound that formed the basis of that album.

Besides drum machines, there were some other electronic percussion devices popular at this time, some of which I believe Ultravox used. One of them was the ClapTrap, an electronic handclap generator, which was developed by Dave Simmons. I wondered if you ever used it, or if you ever used any of those other, more singular devices?

No, I don’t think I ever used a ClapTrap, though I wish I’d had one. Maybe 1979, when Metamatic was recorded, was just before the ClapTrap came out.

I used enjoy making all the percussion sounds on the ARP Odyssey. The bass drum on “He’s A Liquid,” for instance, was an ARP bass drum and sequencer. The clap sound on “No One Driving,” likewise.

You’ve described Gareth Jones, who worked on Metamatic, as a perceptive engineer, who understood the significance of this new technology—drum machines in particular. I assume this means you had some experiences with other engineers and recording personnel who weren't sold on the use of drum machines. If so, could you describe any of those encounters?

Mostly very dispiriting. Recording engineers in those days were often surprisingly conservative—unimaginative and unadventurous.They despised anything radical, distorted—even tended to distrust equipment that was physically small. “What! That? For drums?!!”

That feeds into a larger question, which concerns the attitude at the time in the music industry toward drum machines. Today, we remember Futurism (or at least New Romanticism), but not always, I think, the resistance to drum machines and related technology—the ideas put about that drum machines were costing musicians jobs, and that they weren't “real” instruments anyway.

I wondered if you could speak in some way about encountering such resistance at this time, assuming that you did, and how you responded to it.

I remember a period in 1980 when the BBC and the Musicians Union seemed set against drum machines and synthesizers, on the premise that they were losing jobs for real musicians. Letters were circulated to members, and moves were made to ban them on television. I remember Gary Numan had some trouble with this.

I also remember some discussion with Virgin records that I’d have to record “Underpass” with the BBC orchestra if I wanted to go on Top of The Pops, which really made me groan. Luckily, all this faded, and the BBC eventually accepted it all as inevitable.

Many recording engineers remained patronizing, though. I was often told that synths were not “real instruments,” that drum machines were simply cheap toys, not meant for recording at all, that the sounds they made were not of sufficient “quality.”

I remember these engineers would often employ a sort of grim, silent mode when I persisted. Everything would go very slowly and there’d be a lot of sighing—especially if I wanted to put the drums through a cheap guitar pedal. “What? A flanger! On drums? You know what they say: Phased, Flanged and Fucked,” as I remember one engineer reacting. A bit rich when I was paying for the studio—and his time.

MXR guitar pedals were also seen as low fidelity, but since my early experience with drum machines I’d learnt to disregard spec sheets. I simply listened to everything and chose what sounded best. MXR made radical, powerful-sounding flangers, phasers and distortion pedals—all nice and meaty. They were streets ahead of those mild-sounding hi-spec, engineer darling units costing ten times more—the Eventides, etc.

So naturally I got enough equipment of my own, in order to make demos I could play before a session, to indicate exactly what I wanted. It saved a lot of sighing, but the engagement and energy were still missing.

Then I got Gareth at Pathway [Studios]. He was a light in the dark. Intelligent, perceptive, enthusiastic, and energetic. He loved to experiment and delighted in new sounds and techniques.

Total eclipse of the past. Future here we come.

Tune in for Part II of my interview with John Foxx—coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers.