Everybody knows that one of the worst places on earth to have a conversation is when you’re in the dentist’s chair.

Especially if you happen to have a chatty hygienist. Unless they’re asking questions that can be answered with a nod or a head shake, your side of the conversation has to be carried on in those fleeting moments after a mouth rinse. Better, then, to just stay silent.

But during my last dentist’s visit (full disclosure: an excellent checkup), something happened that I’d never experienced before. Something that demanded I try to keep up my side of the conversation.

Before all the festivities began, I mentioned to the hygienist that I’d recently returned from Japan. And I told her that I was there, in part, because I’d written a book about drum machines.

She paused for a moment, her tools in midair.

“What’s a drum machine?” she asked.

She sounded a little sheepish, as if she should probably know about something that had been the subject of a book. But not sheepish enough not to ask. After all, she was going to be the person carrying on the majority of this conversation.

I was taken aback—but in a good way. No one had ever asked me this question before. And I realized I’d never considered that there are quite a few people out there who might wonder the same thing. Especially now—going on 40 years after the drum machine’s heyday.

“It’s a musical instrument that generates programmed rhythms,” I offered. Lame. A description that doesn’t really help a layperson at all.

Her confusion was evident, even beneath her mask. I tried again.

“A drum machine takes the place of a real drummer,” I said. “You program drum parts into it, rather than have a real drummer play them.”

Better, though kind of reductive. I could see, however, that I still hadn’t succeeded in breaking through. I wasn’t dumb enough to think, “I’m losing a potential reader here!” But I’m stubborn enough to want to inform the public, even on the verge of a teeth cleaning.

Then the radio came to the rescue.

The local Eighties station, on the few occasions I hear it, usually just reminds me that my life has passed on to the “nostalgia” phase in the wider culture. In this case, however, its timing was up-to-the-moment-perfect.

Jody Watley’s 1987 hit “Looking for a New Love” was playing. And before the hygienist could start attacking my teeth and gums, I pointed to the speaker in the office and blurted out, “That’s a drum machine.”

She paused again. “How do you know?” she asked.

In fact, I knew because I talked to the song’s producer, David Z, for my drum machine book. He told me that the massive snare drum sound he created for “Looking for a New Love”—a sound that was envied and copied by many other artists—was the result of an intentional desire to “win” the unofficial competiton that was happening in pop music at the time. That was the race to develop the biggest, baddest backbeat possible— a competition David Z described as “healthy.”

“This was my philosophy: you know in the first two bars because of that snare sound, it’s that artist,” he explained. “Every kick and snare sound defines that artist.”

I didn’t tell the hygienist all that, of course. There was at least a .00001 percent chance she might buy the book. Let her have the thrill of finding out for herself!

More realistically, it seemed like it would be an unfortunate reversal of protocol for the patient—who really isn’t supposed to have a speaking role in this scenario—to bore the hygienist.

But then the next song arrived: ZZ Top’s “Sharp Dressed Man.” And once again, I couldn’t stay silent—even though by this point, we were in the midst of the cleaning.

“That’s a drum machine, too,” I gurgled, with as much gravitas as a man can summon while reclining nearly on his back with a mouthful of suds.

Once again, the hygienist was interested. Or at least, she did a completely professional job of feigning it. She set down her tools and listened for a moment.

“I don’t see how you can tell that,” she said, frowning slightly.

“Most people can’t tell,” I reassured her. For more than four decades, the band, in fact, has kept up the premise that the drums on that song—and on the rest of its multiplatinum parent album, 1983’s Eliminator—were played live. In fact, it’s likely that they were programmed by an engineer named Linden Hudson, a fascinating guy whom I interviewed for my book. He convinced the band that the secret of dance club success was a song that clocked in at precisely 124 beats per minute.

Hudson was right, as the singles that became chart successes proved. If it isn’t his programming on those songs, then it’s probably the work of engineer Terry Manning, who apprently confessed as much years ago, in a blog post that has since disappeared. But it’s undeniable that it was Hudson’s vision that help dust off ZZ Top’s desert boogie and sculpt it into a lean, mean, MTV-dominating machine.

Again, I shared only a fraction of this information with my hygienist. Yet if the world at large remains ignorant of Linden Hudson’s particular genius, I can say at least that someone in my dentist’s office now knows the truth. One heart and mind at a time!

I thought I’d probably done enough by relating Hudson’s untold tale. I felt like I’d performed a good deed. And I needed to get this appointment done and get back to work.

But then came the familiar programmed clave-and-claps beat of “Sexual Healing.” Once again, I realized it was my duty to speak.

I had to bide my time: the hygienist was applying polish of a sickly mint flavor. (It’s better, at least, than sickly vanilla.) But as soon as the water was suctioned from my mouth, I leaped into action.

“That’s a drum machine, too—probably the most famous drum machine of all time. The Roland 808,” I gasped. I didn’t tell her the story of how Marvin Gaye (and, most likely, guitarist Gordon Banks) programmed that beat in a studio in Belgium, where Gaye was living in self-imposed exile. I didn’t say that it was inspired by the reggae Gaye had heard while he was on tour in England during 1981.

Nor did I mention an even further, fascinating tangent: that British soul crooner Paul Young would also use the 808 in a chart-topping cover of Gaye’s “Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home).” That single was first recorded by Gaye all the way back in 1962. Young’s version thus paid tribute to two generations of Gaye’s influence: 1960s Motown, and 1980s drum-machined soul.

(And I refrained from mentioning my meeting with Tadao Kikumoto, the 808’s creator, on my recent trip. I was pretty sure the hygienist, despite her solicitous conversation, wouldn’t care. If you’re reading this, you might. That will be the subject of another post, soon.)

Once again, the hygienist listened. And she then said something that I’ve thought about often over the years—as I imagine a lot of people who are musicians, and who write about music for a living, have done.

“I guess I just can’t pick out things like—drum machines?” she confessed, still unsure about this strange new device we’d sort of been talking about. “When I listen, I just hear music.”

It’s a really smart observation, and one that haunts me when I think about being a kid, and listening to the latest hits on my parents’ AM radio, or their eight-track player—on the way to school. Back then, it was all just music: a block of sound comprehensive and total. I didn’t pick anything out because I didn’t know how. The song—its music, its lyrics, its production and recording, even the way it was transported through the cheap speakers in my mom’s crappy Vega—was a singular thing.

And all the more wonderful, I think, because of that. To be able to go back to that time, when my innocence and ignorance allowed me to perceive the unity, rather than the divisions, in a piece of music—well, I wonder a lot about what that might be like.

Maybe that happens occasionally, still, in the few unguarded moments in our lives. When you’re listening to an unfamiliar piece of music as you drift off to sleep, perhaps, and the component parts blur. Or maybe when you catch a snatch of melody in a shop somewhere on a trip, and you’re too focused on your new surroundings to fully break down the song: “That’s the same chord progression as this Beatles song”; “That vocal melody is being thickened up in octaves”; or “That’s actually a drum machine”—an 808, a LinnDrum, an E-MU Drumulator with “Rock Drums” chips.

But it doesn’t happen much. As we age, many of us who love music get tossed out of our own little musical Eden. The eternal curse of too much knowledge.

And as the hygienist handed me the tooth-shaped card with my next appointment written on it, I figured that maybe we’d both learned something. Who was the more informed listener between the two of us? I guess that’d be me. Who was the happier listener? I wonder.

When I got to the car, I tossed my phone onto the dashboard and looked over my Spotify playlist for a moment. I saw the first three songs and identified the drum machines (or at least, the electronic percussion) responsible for their rhythms.

Like the hygienist, I paused, my hand in the air. And then I decided, for that afternoon, anyway, to listen to a podcast instead.

Tune in for more exclusive interviews about drum machines and electronic percussion, coming soon! Meanwhile, follow me on Twitter (@danleroy) and Instagram (@danleroysbonusbeats), and check out my website: danleroy.com.

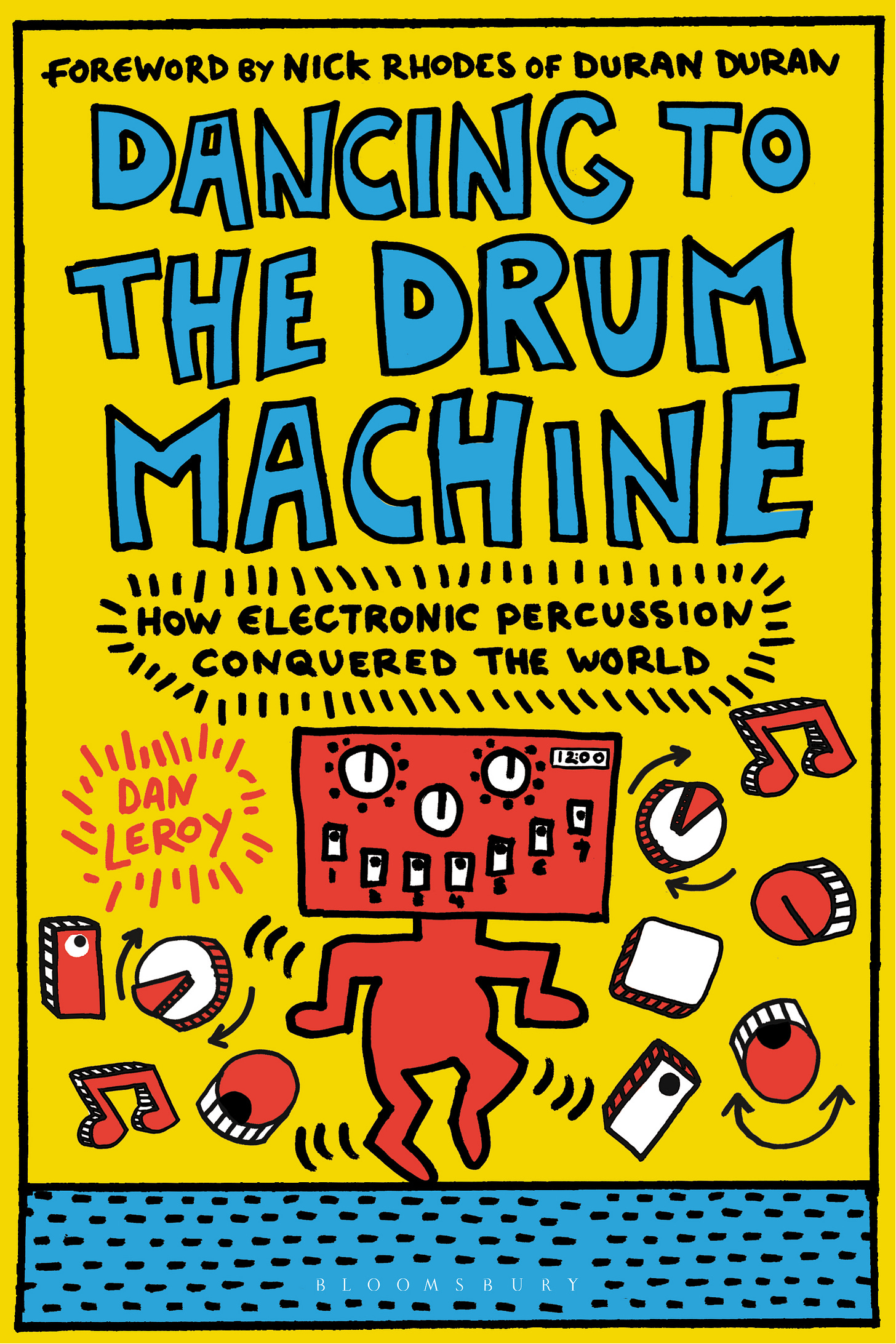

Dancing to the Drum Machine is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle/eBook from Bloomsbury, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple Books, and other online retailers.

Ha! I thoroughly enjoyed reading that!

Thank you so much for reading! Glad you enjoyed it :)